Move over, Netflix. Don’t get me wrong — there’s plenty of perfectly good stuff to stream out there. But if you come to my place, you’ll find MSNBC blaring on my TV. After 30 years as a reporter, old habits die hard. And why would anyone choose the flimsy fictions of Hollywood over the real-life drama of Washington and its cast of characters, including duplicitous Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema the cypher and drecky Steve Bannon?

Which is why the story of Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen was in heavy rotation chez Sachs last month. There she was, in front of Congress, unspooling hour after hour the bad deeds of Mark Zuckerberg, who Grandma Esther would have spotted a mile away as a gonif.

In 2002, while I was working at Time magazine, three women jointly selected as the Persons of the Year were dubbed The Whistleblowers. (Don’t tell me you’ve forgotten their names already — Coleen Rowley of the FBI, Cynthia Cooper of WorldCom and Sherron Watkins of Enron. Ah, fame is fleeting.) Like Haugen, these women had spilled the beans. At the time, the choice struck me as kinda gimmicky, but looking back a couple of decades in the rear-view mirror, it now seems prescient.

Which is why, on October 7 at 6:50 pm, I found myself musing about the virtues of female whistleblowing. (Being able to keep track of dates and times is critical for would-be whistleblowers.) I was waiting for my good friend and fellow journo Evy to arrive for dinner. I never suspected that our meal would mark the nanosecond when I, too, would attain whistleblower status.

The evening began as a rendezvous with indigestion. The plan was for me to meet Evy at Maison de Faux Cuisine (name changed to protect the busboys) on West 73rd Street, in the heart of the Upper West Side. I got there ten minutes early, in hopes of snaring a good outside table, since the pandemic has driven hordes of local diners en plein air.

A dark-haired waiter brusquely took me to the least desirable table in Manhattan. I don’t mean to sound like a kvetch, but the corner of the table had a big chunk missing, and the view was of two wooden sawhorses no one had bothered to drag away after some recent construction. The setting had all of the charm of the Paris city dump.

The waiter who had seated me in this junkheap looked more like a scowling ruffian than an employee in a fine establishment. I’ll admit it — I was scared of him. I summoned up an embarrassingly timid voice and squeaked, “I don’t think my friend Evy will want to sit at this table.” He dismissively mumbled something about the fact that it was the only table available. I spotted several empty tables with stylish bar stools at unchipped tables. What about those? I motioned. “You wouldn’t want to sit there,would you?” he replied. You’re damn right I would.

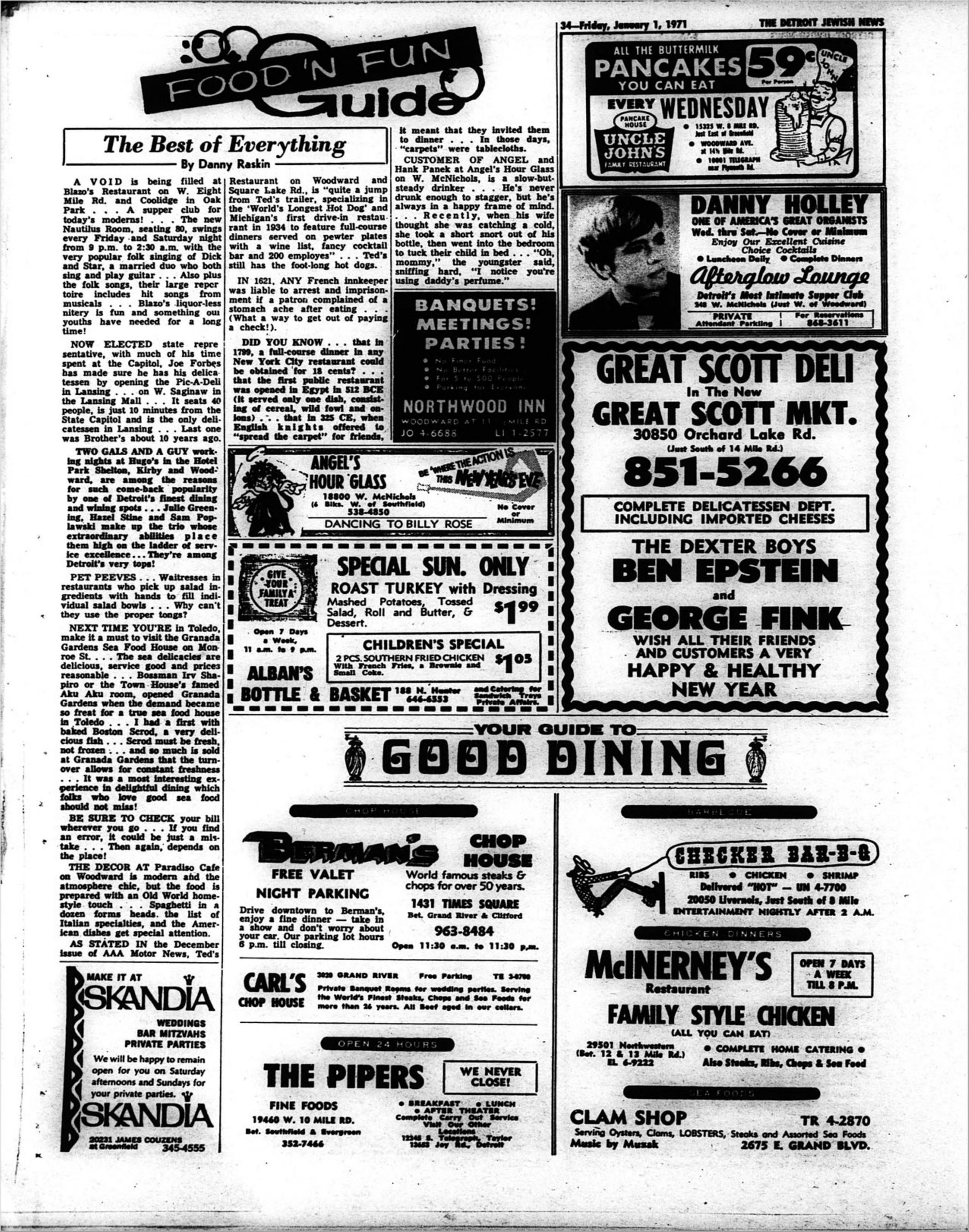

At that moment, the situation was thrown into sharp relief. While I am no nonagenarian, I’m not a coed either. (OPHS, Class of 1970 — do the math.) Evy in absentia and I were getting the treatment that two women alone often get in restaurants once they no longer get carded. Lousier tables, lousier service. Which is plenty ironic, because I am actually quite a good tipper. My experience in high school waiting tables at Blazo’s, a decidedly non-franco eatery in Oak Park, had left me with a permanent sense of sisterhood with servers.

I got a little huffier, determined to assert our right to sit with the rest of the human race during this meal. The waiter got huffier, too — who was this antiquated bitch to be pushing him around? Glowering, he moved me to one of the nicer high tables, just as Evy rounded the corner. Then he dropped only one menu and scooted.

Of course, I told Evy the story when we were sharing our lone menu, and she got the situation immediately. Evy’s no dummy — she’s been an editor at the best publications in the city. Any woman who’s survived those snake pits knows the score.

Prince Charmless came back to our table at this point. He clearly hated me, and I wasn’t the president of his fan club either. But there was work to be done — taking our orders and getting us the hell out of there. Alas, sitting on my hard-won tall chair, the waiter was a few inches away from my nose and maskless when he started to take my order. The last I heard, it was still the pandemic. I wasn’t going to let some bogus garçon spit in my direction. I politely asked him to put on his mask.

He reared back. “No. I don’t have to. I’m vaccinated.”

I was genuinely stunned, as was Evy. In addition to working outside, our waiter was running back and forth into the restaurant and the kitchen. Give me a break — I’ve eaten at plenty of outside restaurants, and the wait staff has invariably been masked. Besides, it was just plain rude, a violation of the server code of servile serviceship I had learned back at Blazo’s.

You want a tip, bub? Put on your damn mask, I fumed silently. With a sour expression on his still-uncovered face, he headed towards the kitchen to get our escargot. (Escargot in both price and pace, but of course not actual snails. The same pretentious dishes served at every joint on the UWS.)

Evy thought that we should stiff the waiter to pay him back for his impudence. But I thought that would play right into his narrative about female diners being cheap, so I talked her out of it. After eating our meals, when we paid the bill — trop cher! — we gave him a healthy tip. But on the merchant’s copy of the charge receipt, I wrote on the back in big letters for his boss’ benefit as well as his own:

NEXT TIME, WEAR A MASK. IT’S THE LAW.

Satisfied that I’d paid the creep back for his incivility, I ran inside the restaurant to use les toilettes des dames before we left. And there, in flagranti, was the scene of the crime. None of the servers, or even the maître d’ at the door, was wearing a mask! Maybe the waiter outside had a colorable claim to be bare-faced, but this was beyond the pale. J’accuse! I tried not to breathe in as I headed for the door.

As Evy and I walked away from the restaurant, full of counterfeit French cookery, we held our heads high. We had been dissed but had risen to the occasion. We made enthusiastic plans never to eat there again soon and said good night.

When I got back to my castle on a cloud, I was still furious with that little twerp and his crappy bistro. I wasn’t done yet. What else could I do to whip that germy place into Covid compliance? With a sense of destiny at my back, I dialed 311, New York City's main source of government information and non-emergency services. I understood down to my toes how Frances Haugen felt when she decided to reveal the treacheries of Facebook to the world.

Mirabile dictu! There was a real human being on the other end of the line. The 311-operator seemed genuinely interested in my sighting and took down the particulars of my story. Like Haugen and my sister whistleblowers before me, I served up each delicious detail with gusto. I would close down Maison Monstrous with my testimony! I imagined Mark Zuckerberg, sitting in the kitchen of the restaurant and cowering when he heard the news that his goose was cooked.

When I was finished unspooling, the operator asked, “Do you want to give your name? It’s not required.” I barely hesitated. Of course! How would MSNBC know how to find me otherwise? I was Case No. 31107938694, a number that clearly indicated a surfeit of diner grievances throughout the city. No matter — I had entered whistleblower history.

My 311-savior said goodbye and told me, “The proper agency will go out and check the situation tomorrow.” Liberté, égalité, fraternité!

I would like to tell you that they perp-walked our waiter down Broadway the next day to loud public denunciations. The denouement, alas, was less dramatic than that. When I called 311 two days later to find out what had happened to Case No. 31107938694, a different person answered the phone. After looking up the case, she told me in a pleasant but perfunctory way, “Thank you for helping keep New York City safe from Covid-19. Thanks for being a good citizen.”

Merde! I would never know the end of the story. Of course, I could walk into the restaurant and see whether they had been forced to wear masks, if not rounded up and sent to the guillotine, but I might run into my adversary sporting a carving knife. I decided to let it go.

I’ll admit it — getting the Big Apple equivalent of a Girl Scout badge was a letdown. My Time magazine cover was nowhere in sight. But as God is my witness, this is only the beginning of my whistleblowing. Next time, I am going to call the Bureau of Dissed Distaff Diners immediately to report any instance of table inequity.

No more being seated next to the broom closet for this gal. Ladies who lunch, unite! We have nothing to fear except the possibility of the evil eye from some surly server or all-seeing eye of Monsieur Meta Zuckerberg.

Fin.

Andrea Sachs is the founder and editor of The Insider, a weekly online publication. She grew up in Oak Park and currently lives in Manhattan.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.