A mural produced by the Detroit Institute of Arts for the Sterling Heights Police Department was recently unveiled — and almost immediately reviled. Even the artist who was commissioned to produce it, Detroit-based painter Nicole MacDonald, says she wants to see her mural painted over.

But life isn’t that simple. Neither is this story.

MacDonald has garnered a respected reputation for painting large-scale portraits featuring the faces of musicians, poets, artists and activists from Detroit, most of them Black, Hispanic and First Nations. Some of her work explicitly advocates for social justice issues, like her Declared Dissent series, which saw the installation of murals espousing universal healthcare coverage and promoting Detroit as a sanctuary city for undocumented immigrants seeking safety and asylum.

But try as you might, it’s impossible to simultaneously “back the blue” and advocate for sanctuary cities. Just look at the set of bills introduced by Michigan Republican state lawmakers in 2019 that were initially dubbed the "Sanctuary Policy Prohibition Acts" before being rebranded as the "Law Enforcement Protection Acts." The way the GOP sees it, prohibiting sanctuary for refugees who might otherwise be assassinated, kidnapped, tortured or raped in Honduras somehow protects police officers in places like Macomb County.

Make that make sense.

So, when I saw that MacDonald had taken on a commission to exalt a police department — any police department — it felt off-brand. On one hand, making a living as a full-time artist is incredibly hard work and I try not to judge how or where artists find income. On the other hand, the Sterling Heights Police Department isn’t just any police department.

In their own ways, the DIA and SHPD are both embattled institutions.

Last June, SHPD added a chokehold-induced federal lawsuit to its sterling reputation.

One month later, a group of former and current Detroit Institute of Arts employees put out a joint statement claiming the DIA was a hostile work environment — one that blatantly devalues people of color.

Millage Spillage

To understand why a globally esteemed arts institution in Detroit is in the business of producing a mural for a police department located 22 miles away in the suburbs, we have to look back at one of the most perilous moments the museum — and the City of Detroit — ever faced.

In 2012, Detroit was in the midst of an unprecedented municipal bankruptcy. An Emergency Manager from Miami had been appointed by former governor Rick Snyder to navigate the city through the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history. At one point, creditors floated the idea of selling off some of the DIA’s masterpieces to pay down what would amount to a fraction of the city’s near $20 billion debt.

But Detroit artists (and art lovers) were not about to let that happen.

Fire breathing dragons were brought in. Really.

To survive, the DIA passed a tri-county millage that provided the DIA with $23 million annually — $10 million from Oakland, $8 million from Wayne and $5 million from Macomb.

But the millage vote came down to the wire that fateful August election night because Macomb county delivered 63,270 yes votes (50.5%) and 61,930 no votes (49.5%).

Yes, you read that right. Almost 49% of county voters told the DIA to drop dead.

The levy costs homeowners about $15 a year for a house worth $150,000. The average price of a home in Macomb County is approximately $193,000. So, 62,000 Macomb County residents didn’t think it was worth 19 bucks a year to have free access to a museum that regularly ranks among the best in the nation.

I’m happy to report the millage was renewed in the primary elections last March by a much wider margin. In the intervening years, Sterling Heights clearly developed an appreciation for fine art, spending some $300,000 of taxpayer money on a sculpture widely known as the Golden Butthole.

Serve and Protect?

As part of its millage deal with the counties, the DIA created the Partners in Public Art Program as an effort to give back to the communities that voted to help keep the doors open.

When Macomb came calling for the DIA’s help in producing a mural, was anyone surprised they wanted to put it on a police station? And did any jaws drop at word that the art would focus on the officers themselves, as opposed to the community they serve?

Hell no, respectfully. You can always count on Macomb to Macomb.

After all, some pundits have suggested the 2016 presidential election that put Donald Trump in the White House came down to Macomb County.

But something did surprise me.

MacDonald’s mural is titled To Serve and Protect, which, for me, always provokes the question: Serve and protect whom exactly?

Joining the mural on the wall of the police station are rows of tiles painted by rows of tiles created by Sterling Heights police officers and their families, with assistance from DIA staff.

Among the tiles painted with outstretched hands, hearts and crucifixes — as if Macomb isn’t home to more than 2,600 Jews, as well as Muslims, Sikhs and some segment of the population that prefers their church and state separate — are a handful of tiles adorned with the problematic Thin Blue Line.

The phrase “thin blue line” dates back to the early 1920s, but a hundred years later, it has been co-opted as a divisive visual symbol. The Chief of Police in San Francisco has banned his officers from wearing it.

Who can forget the violent and deadly “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville? That’s when the symbol went mainstream. That’s when we saw images of thin blue line flags carried next to confederate flags and flags representing hate groups like Identity Evropa.

The message was clear.

Three years later, the Brennan Center for Justice would do the rigorous research to prove what many were thinking: Racists love cops. And many cops are, themselves, proudly racist.

After the 2020 murders of Ahmoud Abery in February, Breonna Taylor in March and George Floyd in May, the Black Lives Matter movement swept across the country as thousands upon thousands of protestors took to the streets to demand justice and systemic reform.

And across the country, police responded to the mass calls to quell police violence with … militarized violence against the very communities they were sworn to serve and protect.

Over the summer, the “thin blue line” visual became synonymous with the egregious and pathetic anti-justice slogan “blue lives matter.” As if a cheap metal badge that can come off in the laundry can be equated with an actual human life.

The dichotomy was set: You’re either fighting for justice for Black Americans, who have been brutally subjugated in this country for more than 400 years, or you’re a boot-licking fascist who’s willing to fight — even kill — to uphold the framework of white supremacy that America was built on.

I said what I said.

Introducing The Punisher

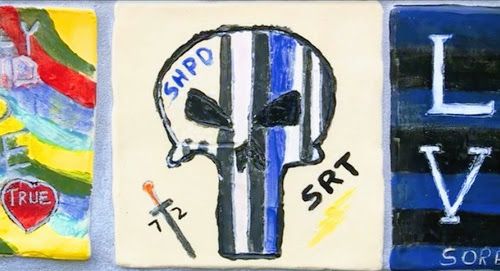

Then the hate iconography (and merchandising) metastasized. And it happened right here in our own backyard. Hate groups had already co-opted the foreboding skull logo of Marvel comics vigilante The Punisher, to the chagrin of its creator. And the Anti-Defamation League, which has deemed it a hate symbol.

But that didn’t stop West Bloomfield’s own shameless opportunist Andrew Jacob — who was already cashing in on selling thin blue line flags to the swelling alt-right tantrum — from capitalizing off the hate symbol by doing away with any lingering ambiguity and combining the thin blue line with the punisher skull.

This newly meshed "logo" can only be interpreted one way: Those who employ it proudly as a facemask, window decal or flag proudly uphold the tenets of white supremacy and honor police as the physical instrument — the modern Schutzstaffel — legally sanctioned to impose it on people of color.

I must not be entirely jaded because I was a bit surprised to see the thin-blue-line-punisher-skull painted on one of those tiles. But hadn’t the DIA sanctioned all the art, not just MacDonald’s mural? Would the police really be so brazen as to feature a symbol of white supremacy? Yes, and yes.

I got a better look at the tile when one of my favorite Detroit reporters, Violet Ikonomova, wrote about the whole fracas for Deadline Detroit. On one side of the skull is a sword with the numbers 7 and 2. On the other side of the skull are the letters SRT above a single lightning bolt.

I have no idea what either of them are supposed to mean. What I do know is that if I saw two lightning bolts, you would likely find me inside the building being charged for destruction of public property.

Postscript

While I was writing this essay for Nu?Detroit, the Detroit Institute of Arts and City of Sterling Heights were in the process of removing the hate tile, claiming ignorance as to what the symbolism of the thin-blue-line-punisher-skull meant. I don’t buy it. My hunch is that somebody involved in the process had to know what it meant but was too afraid to question authority.

Speaking of questions, I find it quite disappointing that several art professionals obviously failed to question the meaning of an “art piece” and the intentions of “the artist.” Like, that’s an integral part of the job, y’all.

So, how can municipalities and arts organizations do better? First, do no harm. The Anti-Defamation League keeps a robust database of hate symbols. More importantly, if you're serious about public art, engage the public – early and often.

Travis Wright is an award-winning writer & multimedia producer who has covered Detroit arts & culture for more than a decade in both print and radio.

Header Image: ribbon-cutting (image adapted from DIA Instagram post)

Footer Image: Marvel Punisher skull logo on DIA police mural (screen grab, City of Sterling Heights video)

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.