It was August 15, 1954. Louis, affectionately called Louie, was 36 and Rosa was 29. As in previous summers, they rented a cottage on the Cass Lake. Rosa’s parents, who lived with the family, vacationed with them as well. Much time was spent enjoying the beach and the warm weather with their two young sons, Marty and Sandy. Rosa was three months pregnant with their third son, Jay.

Louie would commute back to the city for work during the week and spend weekends at the cottage. Their family business, a tailor and dry-cleaner, was located on Dexter and Burlingame in Detroit. Alterations and custom clothing were skillfully completed by his father-in-law while Louie’s business acumen provided the backbone of their partnership. Their combined skill set was the recipe for a successful establishment.

On that ill-fated August afternoon, Louie decided to dive off a raft into the cool, refreshing water. He broke his neck and was immediately paralyzed. He sustained an irreparable injury and was medically labeled a C5 quadriplegic.

Marty told me, “Believe it or not, at two and a half, I have a distinct memory of climbing up on an outdoor picnic table and seeing all of the people gathering around and an ambulance with its lights flashing. I don’t believe I witnessed them taking him out of the water to the ambulance. I also remember that he was in the hospital for months, but to a child my age it was forever.”

After a prolonged hospital stay, Louie was transferred to the Rehabilitation Institute of Medicine (RIM). He remained there for months on end. After intense treatments at RIM, Louie spent several months at a clinic in Warm Springs, Georgia, that FDR had established for his polio rehabilitation.

Louie's doctors instructed Rose to institutionalize her husband. She refused outright.

When I asked Marty how he dealt with his dad’s absence he recalled, “I knew he was in the hospital for months. To a child my age it was forever. There was a time I would write him letters. What I mean is that I was still too young to write, but I remember taking pencil to paper and drawing what I thought was legitimate writing. When my dad finally returned home, I was completely surprised that I had forgotten about him, and I felt extremely guilty over that.”

As it turned out, guilt also played a role in Louie’s life. He was born in 1918 in Kazimierz Dolne, on the Vistula River, a small resort town in Poland. It had a large Jewish population, and Yiddish was the primary language. Louie was the middle of three brothers, and they had a large extended family.

The family owned a produce business. Louie worked at the town bank where he became proficient in using the abacus. At a young age, he became a philosophic ‘communist’ as did many Jewish youth, and left home to go to Mother Russia where he thought he would find a worker’s utopia. Instead, as a result of being Jewish, he ended up in a labor camp in Siberia, just like the one described in the Solzhenitsyn novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. (A fellow prisoner Menachem Begin, would become the sixth Prime Minister of Israel.)

Louie remained in Siberia for almost two years until the camp was disbanded for political reasons. After his release, Louie made his way to Asia Minor, evading the Nazis and found a job in the produce business. He was the sole survivor of his family.

Marty commented, “My dad always thought that his accident was repayment for not taking his younger brother with him when he left Poland before his entire family was wiped out. This, in spite of the fact that he readily believed his very genteel younger brother would never have survived the labor camp in Siberia.”

Rosa was also no stranger to tragedy. Born in Kiev in 1925, Rosa Radomisielsky grew up across the street from the NKVD central office, the precursor to the KGB. Her father was a tailor and, as an only child, Rosa was accustomed to the refinements of big-city life. Russian her primary language, Rosa grew up believing all the information delivered from Stalin’s propaganda machine.

Everything quickly changed when Rosa’s parents decided to leave Kiev just before the Nazis arrived. The entire Jewish population was marched to the nearby town of Babi Yar. They were all shot and left to die in large ditches by the roadside. Marty was named after Rosa’s grandmother Miriam, who was one of the victims of Babi Yar.

Rosa’s family made their way to Asia Minor, where she became a secretary to the manager of a produce business — Louis Levinson. There was an instant attraction. But he had a girlfriend back home. As the months passed, Louis discovered that she had perished in the war.

Rosa and Louie married in 1945. They obtained forged papers claiming to be Greek citizens. They left Russia, along with Rosa’s parents, and eventually ended up in a Displaced Person’s Camp outside of Salzburg, Austria. The couple passed on a chance to go to Palestine, not wanting to leave Rosa’s parents. Detroit became their destination since a relative was living there.

Rosa and Louie were well acquainted with difficult situations. Louie’s accident was another chapter to be written. After the shock and anger subsided, there was little time for Rosa to reflect on dreams deferred. She had to shift into high gear for her family. With minimal support available once Louie came home from rehab, Rosa worked hard to put the situation in order.

They converted a first-floor den into a bedroom with a hospital bed. They built a wooden ramp at the back of the house. Eventually a visiting nurse, Miss Pat, came to the house on a regular basis for home care and the Levinson boys bonded with this loving lady. Says Marty, “We continued a relationship with her until her death. My parents went to her wedding, and we visited her at her home when she had a baby.”

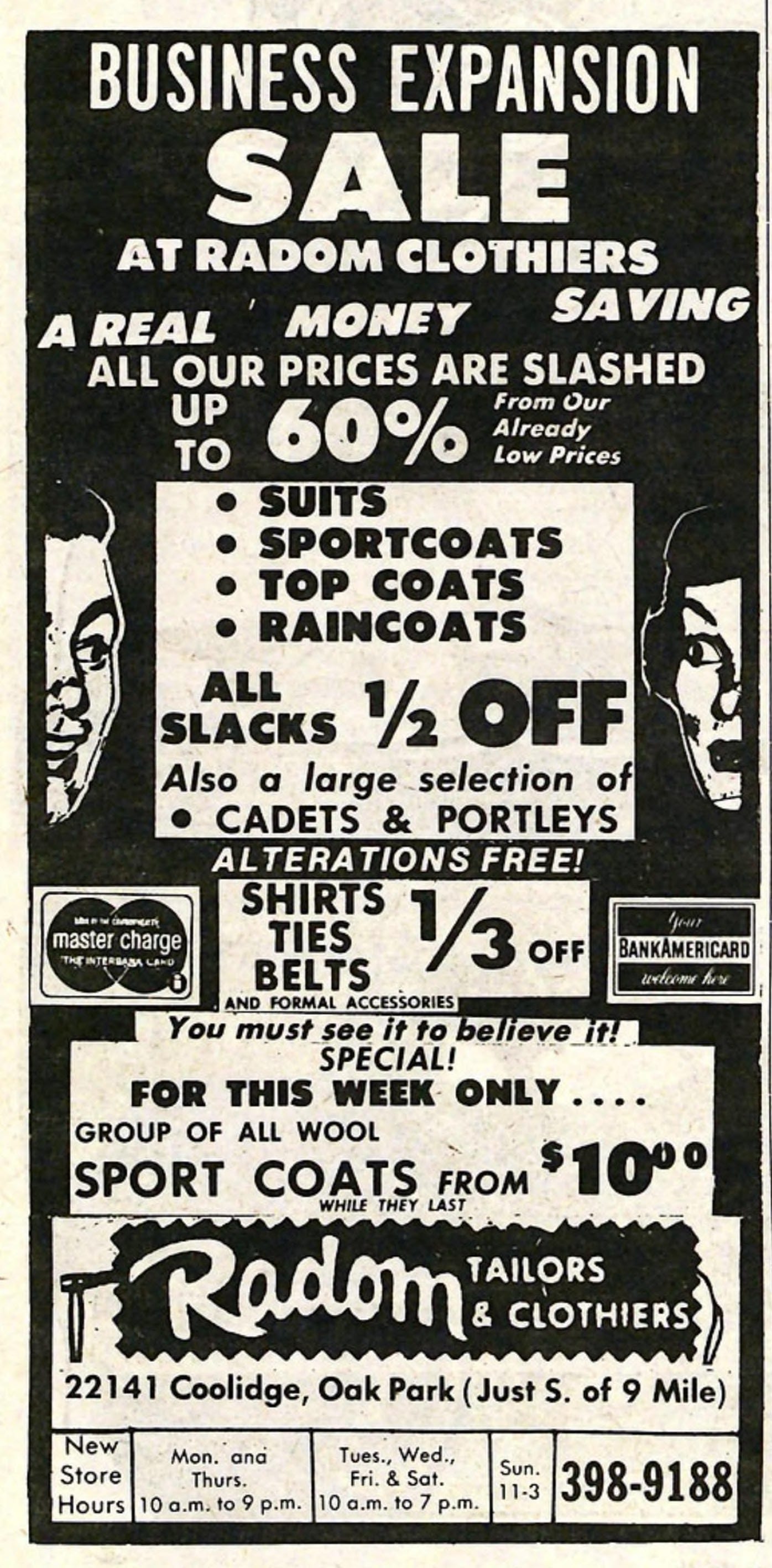

Rosa’s mother cooked meals and cleaned, and when the timing seemed appropriate, Rosa took over Louie’s place at the shop and worked every day. Their business expanded and moved to Coolidge and 9 Mile in Oak Park. They now carried menswear and offered tuxedo rentals. Radom Tailors became the iconic Radom Clothiers — the place to go to for men’s apparel.

At this juncture there was a need for outside help. Hourly workers were hired. But when staff didn’t arrive, the young Levinson boys would be in charge. This situation prompted Rosa to hire live-in staff to oversee Louie’s needs.

Marty remembered, “A series of African American women cared for my dad. Me and my brothers became very close to them. They taught us card games, including poker. Eventually we switched to a six-day week live-in with women from Poland since my dad spoke Polish. They were various ages and would stay for a year or more at a time. They could earn more in a month from us than in a year in Poland, and they would send money back home.”

Even though caregivers became like family, chronic pain was Louie’s constant companion. He suffered from complications associated with quadriplegia and awoke nightly from dreams of the war. Doctors were consulted on a regular basis. Rosa became proficient in administering injections and Marty even learned this skill as a teenager. Marty said, “Many specialists in the field do not believe me when I claim that a quadriplegic from 1954 lived for 34 years. I’m told it’s virtually unheard of.” Even so, Louie had all the right ingredients to persevere — strength, stamina, and a loving, committed family.

Louie returned to his beloved store when Marty and his brothers were all quite young. He stayed until closing every night. Even though Louie was a stationary figure in the store, he had total recall of stock and exactly where specific pieces of clothing could be found. Louie became the conductor in a finely tuned orchestra of salesmen. This included Marty and his brothers. Says Marty, “We all cut our teeth working at the store on weekends and over the summers. My dad knew the customers so well and could direct the employees where to go in the store. He and my mom managed the business side of the store together.”

While at work, Louie manned the phones — thanks to a surgical procedure on his left hand. Marty explained, “A tendon was transplanted on his left hand so that when he’d drop his hand on the phone receiver, by extending his wrist, it would pull his thumb to close around it so he could pick it up. My main two jobs for him were dialing the rotary phone, either at work or at home and setting up his cigarette in a holder, that he could actually hold and then I would light it. When my dad finally gave up the habit, I was out of that job. Through a friend, we were able to get a prototype push button phone before they were available to the public. People would come over to our house just to see the fancy phone. He could use his thumb to dial numbers, and I was out of another job.”

However, Marty was later promoted to a position that gave him much satisfaction. Louie arranged with a neighbor, who was a policeman, for Marty to get an early restricted driver’s permit before his 15th birthday. He could drive his dad to and from work but was not allowed to drive without an adult in the car. Marty said, “It was still cool to show off that I could legally drive.”

In 1964 the Levinsons moved to a custom-built home in Southfield with accommodations for Louie. The garage included a cement ramp into the house. However, getting in and out of the car posed challenges. Marty discussed the various methods that were employed over the years. “Initially, we had a pulley system with a hook that was installed on the roof of our car. We’d put one pad under my dad’s legs and another behind his back, then hook them up to the pulley, using it to lift him out of the chair and swing him into and out of the car. Eventually we got a hydraulic lift that replaced the pulley. Finally, we bought a van in which we removed the middle seats and built ramps to push him into the car and lock his wheelchair in place. Later we installed a hydraulic lift for the van. This would draw crowds and oohs and aahs wherever we went. It actually proceeded the show Ironsides.”

When the workday ended for Rosa at the store, she switched gears. She was ahead of the times with an after-school program set in place for her sons. Russian was their first language in the house and when these skills began to wane, Rosa would tutor the boys on a one-to-one basis. Reading and writing were also on her agenda and the boys’ study skills ramped up. Rosa’s efforts paid dividends. Marty became a pediatrician, Jay a gastroenterologist, and Sandy hit a double — a research scientist and patent attorney.

As a matter of fact, Jay occasionally sees patients that were former customers of the store. He would tell Marty about these encounters (with the patient’s permission). According to Marty. “A prime example was when Jay did a colonoscopy on one of our steady customers, Mr. Schwartz. I would then ask — which Mr. Schwartz? 42 short or 44 long?”

According to Marty, “My brothers and I seemed to do all the activities that all our peers did, and more. In addition to regular sports, Jay and I took tap dancing lessons weekly for years and performed at various venues including local TV. Looking back, my mother would come home from work, wolf down a quick dinner and then take us to tap dancing. Every summer we took family vacations together, with my mom, brothers and grandparents. We traveled to South Haven; the Catskills and we even took the van all the way to California. My dad would stay at home to run the store. For those two weeks, he had to recede back to being lifted into a car. In retrospect, I have always wondered how the hell my mom and dad were able to do all that.”

There was never a lack of leisure interests for the Levinson household. When Marty was still a child his parents wrote a musical from a short story by Sholom Aleichem. They transformed it into a Yiddish play since this was the uniting language of refugees from Europe. Rosa had to quickly learn Yiddish when she and Louie arrived in the United States. They also founded the Albert Einstein lodge of B’nai Brith. The group was mainly comprised of Jewish refugees in the Detroit area.

In 1968, when Marty was 16, he accompanied his dad and one of his caregivers on Louie’s first trip to Israel. He took a one month hiatus from school during his junior year. Marty’s involvement was priceless on such a challenging and lengthy trip. Marty remarked, “I had no idea it would be a life altering experience. I met people from my dad’s hometown, close friends from their time in the DP camp in Austria and the family of a person who was much later ascertained to be the only living relative of my dad’s family. I also bonded with Israel and my Jewish heritage.”

When I asked Marty about the impact of his dad’s accident he remarked, “It clearly gave me a perspective on life that none of my peers had. The strength and perspective allowed me the ability to deal with my own son having lifelong disabilities. It clearly inspired me in my career choice and my drive to be good at it. I constantly feel that my existence has to represent and preserve the legacy of my parents’ families.”

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.