This deep dive is from Detroit Urbanism. If there are places or moments where your Jewish geography crosses paths with the city's history, we'd love to hear about them.

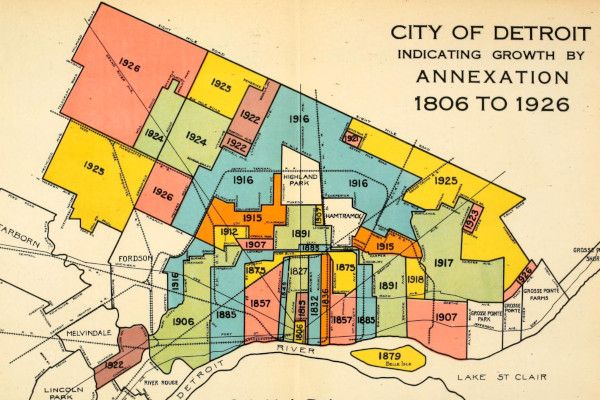

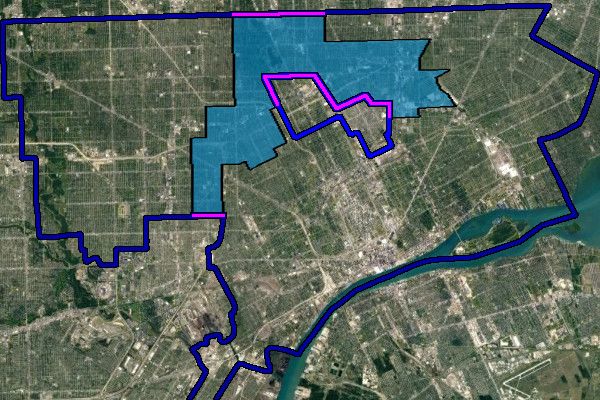

One of the first things you probably notice about the map of Detroit is that there are two large holes in the middle of it created by the cities of Highland Park and Hamtramck:

These two communities were encapsulated within Detroit's borders when the city annexed land from Greenfield and Hamtramck townships in late 1916. Although technically comprised of five distinct annexations, taken together they covered more than 21 square miles, making this the largest addition to the city until that time, and being surpassed only by a massive Redford Township annexation in 1926.

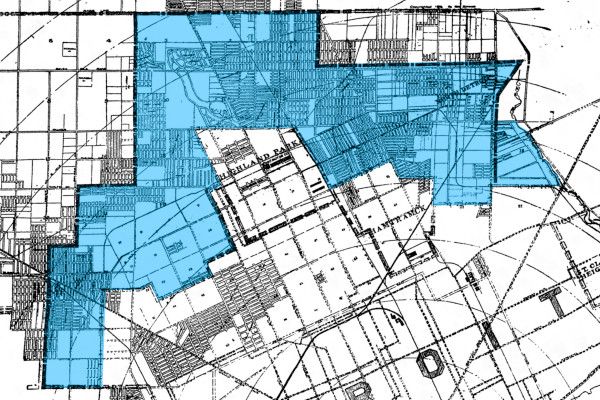

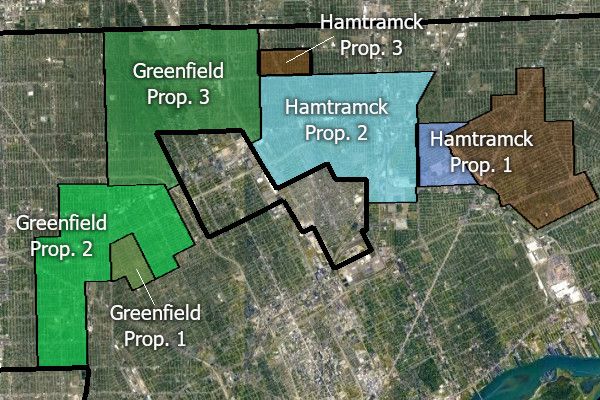

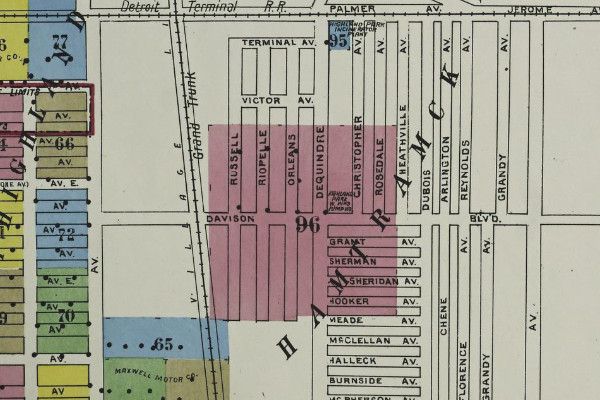

The map below shows local municipal borders as they existed just before the Greenfield and Hamtramck township annexations were made official in December 1916.

Detroit was quite dense at this point in its growth, containing an average of 24.62 people per acre. It was the fourth densest US city, after Baltimore, New York, and Boston. Today, by comparison, Boston contains 22 people per acre, and San Francisco 29. Detroit's average density is now fewer than eight people per acre.

This congestion inevitably resulted in the subdivision rural township land just outside of Detroit's city limits. Most of the lots north of Highland Park and Hamtramck had long since been sold by 1916, but the townships were unable to fund the installation of public utilities. "Sewerage is the all important question for scores of Detroit real estate men who own subdivisions" in the annexation territory, the Detroit Free Press wrote. "It is claimed that lack of sewerage is all that is holding back construction of thousands of homes in this district. The construction of sewers on a large scale will be a big burden for the city but, it is countered, the tax rolls will benefit by unnumbered thousands of dollars as soon as the purchasers of property in the district are able to begin work." ("Voters Adopt 4 Annexation Plans; 3 Lose." Nov. 15, 1916.)

In August 1916 it was reported that "representatives of real estate men and citizens of the territory affected have circulated petitions" calling for multiple annexations to Detroit. ("Plan May Bring Village In City." DFP, Aug. 10, 1916.) Later that month, the Wayne County Board of Supervisors received the petitions, containing approximately 7,000 signatures, for seven proposed additions to Detroit totaling 27.55 square miles. At their September 26 meeting, the board approved placing all seven proposals on the ballot at the general election of November 7. One proposal, from Springwells Township, was rejected at that election, and will not be covered here. The remaining six proposals — three from Greenfield Township and three from Hamtramck Township — are discussed below.

Greenfield Proposal No. 1

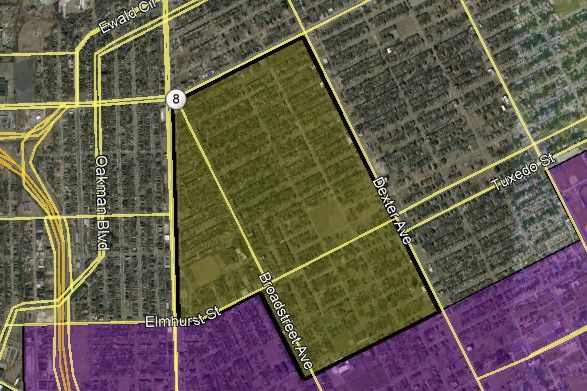

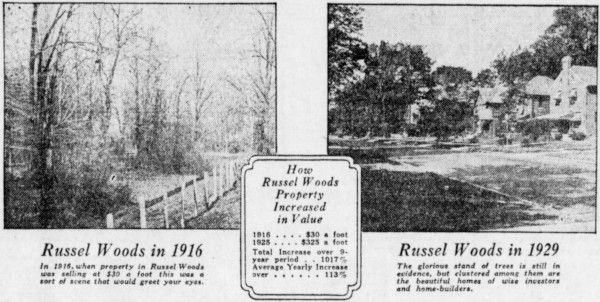

"Russell Woods"

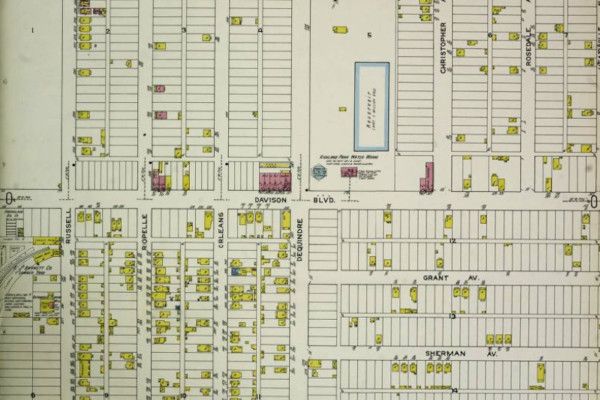

This 0.6-square-mile area contains the original plat of Russell Woods. Covering nearly one-third of this area, Russell Woods was platted in March 1916, just eight months from the annexation vote. When the real estate concern, Will St. John & Company, put the subdivision on the market the following month, every lot was sold out in three days. ("721 Lots Sold in Three Days." Detroit Times, Apr. 10, 1916.)

A smaller part of this annexation territory was platted in May 1916, as Robert Oakman's Galvin Park Subdivision. The map below shows all subdivisions contained within this annexation area, with the year the subdivision plat was filed with Wayne County.

Only seven votes were cast in this area on November 7, 1916: six were in favor of annexation, and one was against. The remainder of Greenfield Township also approved, voting 3,265 to 959 in favor. In Detroit, the measure passed by 81,151 to 11,603.

Greenfield Proposal No. 2

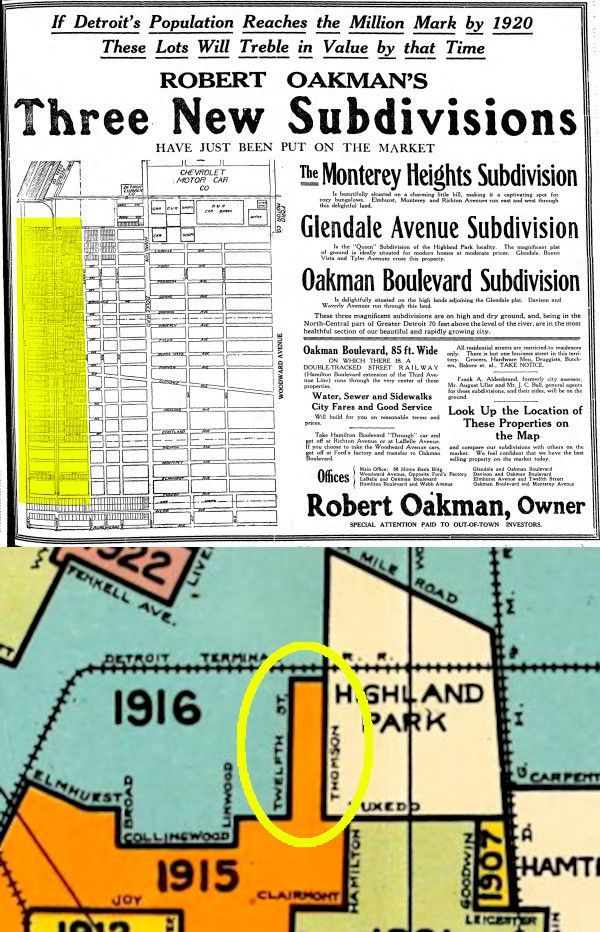

"Oakman Boulevard"

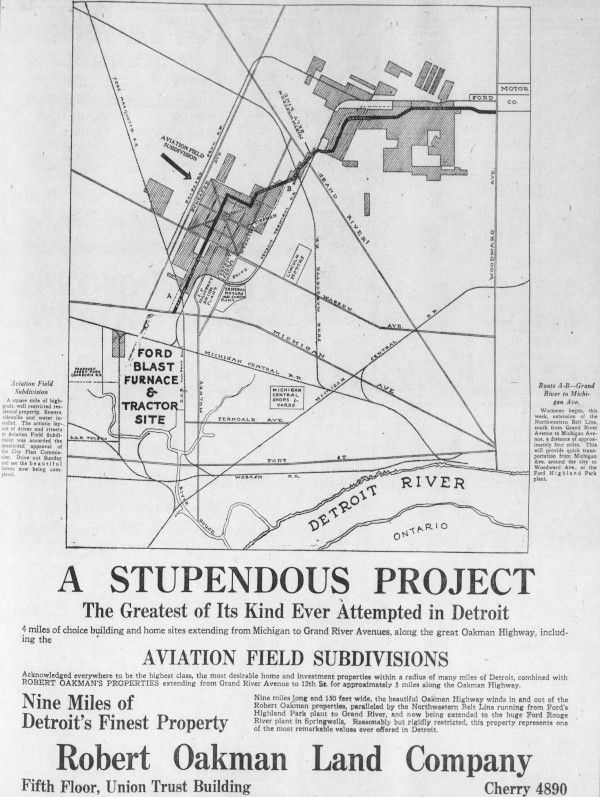

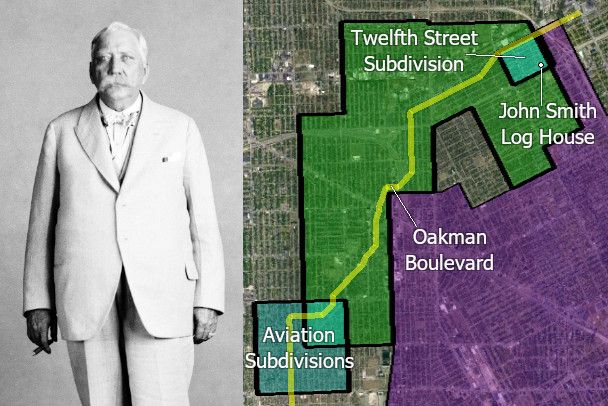

In March 1916, real estate developer Robert S. Oakman announced that he had acquired enough land northwest of Detroit to establish a twelve-mile-long boulevard for the city. Originally called the Ford Highway, it offered a convenient shortcut between two of Henry Ford's most important sites: the Highland Park assembly plant on Woodward Avenue, and the new farm tractor factory in Dearborn, which would later become the River Rouge Complex. The thoroughfare would also serve as a convenient link between the spokes of Woodward, Grand River, and Michigan avenues. The Ford Highway has since been renamed Oakman Boulevard.

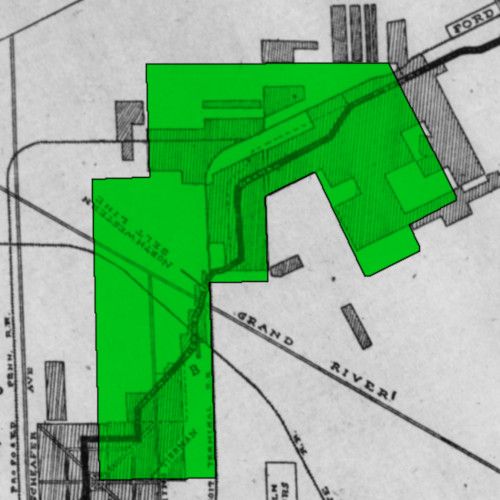

Below is a superimposition of Greenfield Proposal No. 2 over the map of Robert Oakman's properties from the advertisement above.

In anticipation of annexation, Oakman planned to lay 40 miles of sewers, grade 50 miles of street, and pour 100 miles of concrete sidewalks in his subdivisions by the end of the year. ("Land Improvement Costs $1,000,000." DFP, Jul. 30, 1916.) An advertisement from March 1916 described many of the features of the new 150-foot-wide boulevard:

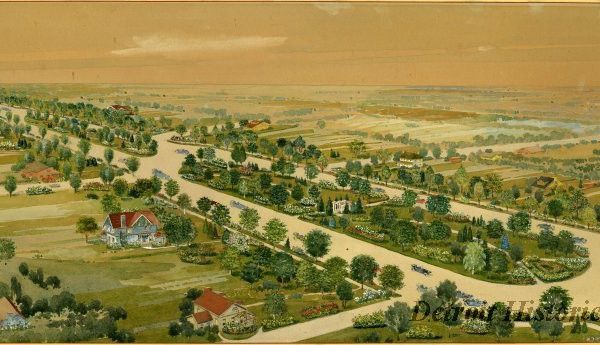

The highway will be double-tracked and a street railway system will operate over it from Woodward avenue to Fort Street... It will be lined with shade trees and made as attractive as landscape artists can make it. It will be one of the new show places of Detroit ... a boon to drivers of automobiles.

This was not the first time that Robert Oakman was involved in an annexation of land to Detroit. In 1913, Oakman and others paid a team of 60 men to circulate petitions to annex all of Highland Park and the part of Greenfield Township east of Twelfth Street. The workers were paid one cent per signature. ("3,000 Detroiters Favor Annexation." DFP, Sep. 4, 1913.) However, the Wayne County Board of Supervisors rejected the petition, going so far as to challenge the constitutionality of the Home Rule City Act of 1909, the law under which several annexations had already been made to the city.

Oakman sued in Wayne County Circuit Court, which sided with the board of supervisors. The case was appealed to the Michigan Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled in Oakman's favor in April 1915, upholding the constitutionality of the Home Rule City Act of 1909. Although the attempt to annex Highland Park was dropped, the board of supervisors agreed to place one of Oakman's annexation proposals on the ballot. Consisting mostly of subdivisions owned by Oakman, the annexation won voters' approval on November 2, 1915.

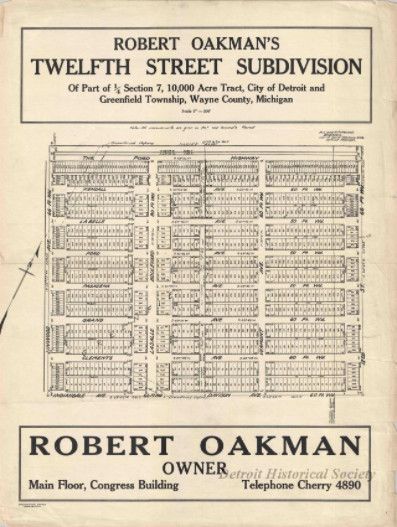

With the idea of annexing Highland Park now forgotten, Oakman focused on annexing his vast holdings surrounding the "Ford Highway" project in 1916. The first development offered for sale in the annexation area, located at the east end of the tract, was Oakman's Twelfth Street Subdivision. By October 1916, the subdivision had water mains and sewers installed, every lot was sold, and more than fifty houses were under construction.

But there was one house in this subdivision that was built before the plat was even drawn. Whether it was somehow intentional or purely coincidental, a small log house once belonging to Greenfield Township pioneer John Smith ended up in the middle of Lot 68 on Clements Street. Constructed parallel to Glendale Road's original east-west orientation, the log house was left intact as the street slowly filled up with houses facing a different angle.

A satellite view of the neighborhood with an 1860 map superimposed.

Oakman pressed on with the installation of water mains and sewers throughout his properties ahead of the election of November 7, 1916. "The way Detroit is proceeding to help the newly annexed sections should convince anyone of the importance of the annexation propositions that will go to the voters next Tuesday," Oakman told the Detroit Free Press. "That section will build up twice as rapidly if annexed to the city helping in a great measure to solve the present housing problem, so I am urging all my friends to remember this fact when they vote Tuesday." ("Sewer and Water Extensions Go In." DFP, Nov. 5, 1916.) Residents of Oakman's proposed annexation voted 121 to 24 in favor of joining Detroit, and it easily passed in Greenfield Township outside of this area (3,068 to 946) and in Detroit (81,183 to 11,753).

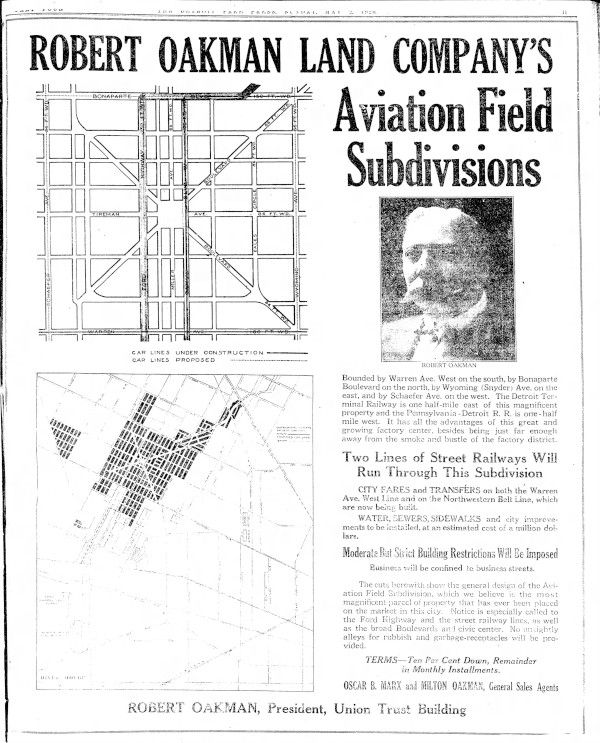

Out of necessity during the First World War, the US government leased some of Oakman's land just outside of the annexation area to use as an aviation facility. Originally called the Detroit Aviation Acceptance Field, it was renamed Morrow Field after Lieutenant Karl Clifford Morrow was killed in an airplane stunt during an Armistice Day celebration on November 11, 1918. The government's lease ended the following year, and Oakman gradually subdivided the property and adjacent land to the north into the Aviation Field Subdivisions. Lt. Morrow's memory is preserved in the name of one of the subdivision's streets, Morrow Circle.

By the time Oakman died in 1942, he had sold more than $35 million of Detroit property, on which $300 million in buildings were constructed, according to his obituary. The inscription on his crypt in White Chapel Memorial Park Cemetery in Troy reads:

He visioned, builded, and bequeathed,

to realize his ideal of a great and beautiful metropolis,

for the city of his birth Detroit

Greenfield Proposal No. 3

"Palmer Park"

Conveniently located on Woodward Avenue, this territory had been eyed by real estate developers since the late 1880s. Real estate developer Robert E. Hull platted the Jerome Park Subdivision here, on the north side of Six Mile Road and east of the Detroit, Grand Haven, and Milwaukee Railroad tracks in 1889. Like Saint Clair Heights, Jerome Park was intended to be a streetcar suburb. For 7½¢, residents could board a train at the Brush Street Depot (the present location of the Renaissance Center), travel up what is now the Dequindre Cut, and exit at the Jerome Park Station, constructed by the developer.

It was advertised as "the finest location for suburban homes, combining the peculiar advantages of health, comfort and cheapness, with the further advantage, being outside the city limits, of a merely nominal rate of taxation." Although Hull reported having sold 235 lots by June 1891, there appeared to be only minimal building activity for many years.

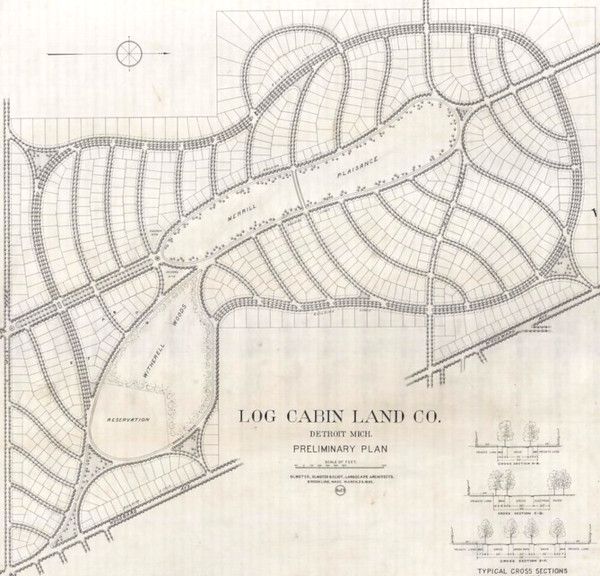

An even more ambitious project was in the planning stages just across Woodward Avenue, on the 700-acre Log Cabin Farm, the summer residence of Senator Thomas W. Palmer and his wife, Elizabeth Pitts Merrill Palmer. In January 1893, Senator Palmer announced that he had agreed to sell most of the farm to a syndicate of real estate investors.

"It is intended to make the farm a perfect suburban city, in conformity with Senator Palmer's idea," the Detroit Free Press reported. "The land will be platted into half-acre lots and will be scientifically laid out under the direction of F. L. Olmstead. A water works and an electric light plant will be established, which, with the continuous rapid transit, will make it a desirable location." ("It Is Accomplished." Jan. 3, 1893.)

The Log Cabin Land Company was organized in February 1893, with Palmer serving as president, and real estate dealer John W. Simcock serving as general manager. State Senator Lewis C. Hough introduced a bill to incorporate the village of "Witherillwold" in this area, but it never came to pass. ("A Great Flood of Bills." DFP, Feb. 22, 1893.) Frederick Law Olmsted visited the site later that month, and by May his firm — Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot — signed an agreement with the Log Cabin Land Company to produce a general subdivision and landscaping plan.

Senator Palmer's estate was shaping up to be a perfect location for an exclusive subdivision of restricted home sites, where wealthy residents would benefit from expensive extensions to city services while paying minimal property taxes to an outside township. Detroit had just completed a $300,000 sewer to the Highland Park border in 1892, and replaced Woodward Avenue's horse-drawn streetcars with new electric models in 1893. The Detroit Citizens Street Railway Company, one of the investors in the subdivision, extended service that year by almost one mile in order to reach the property.

Although it had not yet been announced publicly, Senator Palmer was planning to "donate" the 120-acre park at the center of the high-class Greenfield Township subdivision to the City of Detroit. The State of Michigan enacted special legislation in May 1893, empowering the city to accept donations of land outside of the city limits for park purposes. This law also "let" the city to station police officers in parks outside of the city limits, and to extend fire protection, public lighting, water supply, and sewer service to them. (Act 404 of 1893.)

Late that summer, Senator Palmer hosted an extravagant luncheon at his estate, inviting the mayor, aldermen, heads of several city departments, and members of the parks and boulevards commission, so that "each of them might see for himself of what Palmer Park consisted." ("Palmer Park Visited." DFP, Sep 2, 1893.) In April 1894, Senator and Mrs. Palmer deeded the park site to the city, reserving for themselves a portion of 12 acres surrounding their famous log cabin for the remainder of their lives. The Palmers' actual residence was on Woodward Avenue, where the Detroit Institute of Arts now stands, but they used the log cabin for entertaining and as an occasional summer retreat.

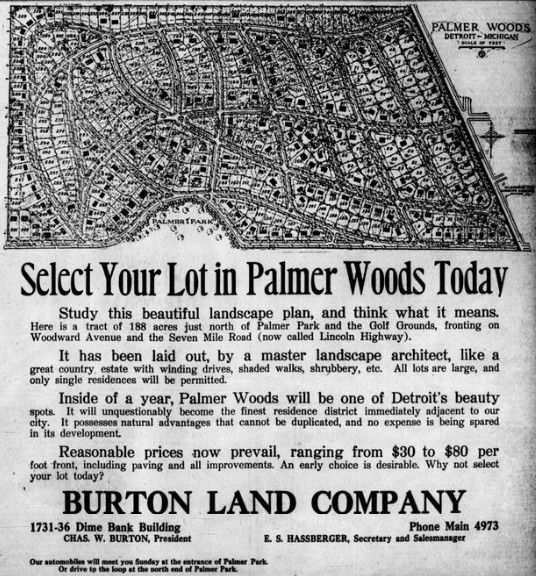

Senator Palmer never saw the completion of his subdivision project. The Panic of 1893 — the worst economic depression the US had yet experienced — broke out just as the Log Cabin Land Company began to carry out its plans. The Palmers turned over their small reservation within the park to Detroit on December 14, 1895. The west portion of the subdivision was leased to the Detroit Golf Club in 1900. The Burton Land Company resubdivided a portion of the Palmer estate north of Seven Mile Road in 1915, two years after the Senator's death. Rebranded as "Palmer Woods," the subdivision was designed by landscape architect Ossian C. Simonds of Chicago.

Part of the Palmer estate, lying east of Palmer Park and south of Seven Mile Road, was condemned by the city to enlarge the park in 1921. Although the city paid a large condemnation reward for the land (more than $1 million), the beneficiary was the Merrill-Palmer Motherhood and Home Training School, established by a bequest of Mrs. Palmer, and to which she left her vast fortune, including this land. Now known as the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute for Child & Family Development, the organization has been dedicated to research and education on childhood development for more than a century.

Although the original scope of Senator Palmer's subdivision was never realized, we have to give him credit for ingeniously imprinting a lasting reminder of his legacy upon the city map itself. Palmer Park will long remind us of the senator, standing up proudly among his many achievements.

The other half of this annexation area — across Woodward Avenue — developed very differently. Almost all of the subdivisions along the east side of Woodward were platted soon after Henry Ford's Highland Park factory opened in 1910, which within six years would employ 25,000 workers. Many property owners built houses in these subdivisions before utilities were even available, choosing to put up with the "drawbacks" of suburban life, including "going to the well for water, draining into cesspools, fussing with stoves which burn liquid fuel and cleaning lamp chimneys." ("Annexation To Add 27.55 Square Miles To Detroit's Area." DFP, Nov. 6, 1916)

With both sides of Woodward Avenue desperate for infrastructure that the township couldn't provide, residents petitioned to incorporate a six-square-mile village, bounded by Eight Mile, Dequindre, McNichols, and Livernois roads. Two names considered for the village were Palmer View and Woodlawn. ("Would Incorporate Part of Township." DFP, Sep. 12, 1915.) However, the Wayne County Board of Supervisors rejected the petition because the petitioners were using a process prescribed under a defunct law. The Detroit Free Press reported:

"A majority of the supervisors were only too glad to reject the petition, according to Alderman James Vernor, because they do not want any more villages on Detroit's borders. (...) Alderman Vernor declares that villages have a habit of incorporating for improvements, and then overbonding, after which the real estate men who have profited by the improvements get out from under, leaving Detroit to take care of the bonds dumped upon it when the villages eventually becomes [sic] annexed. Vernor thinks that there should be a law, forbidding incorporation of territory as a village unless it was over five miles from the city."("Incorporation of Another Detroit Suburb is Foiled." Oct. 26, 1915.)

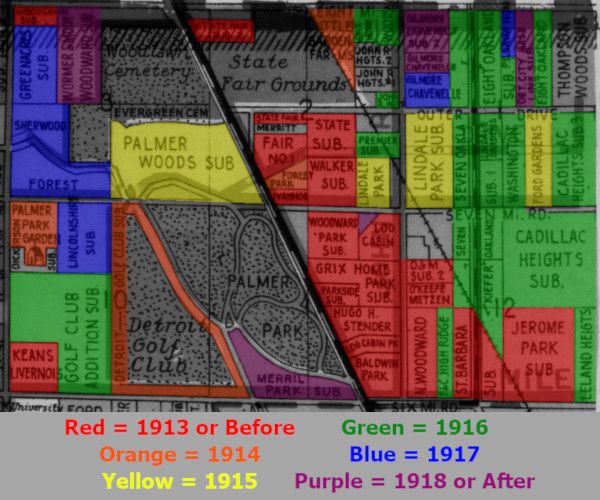

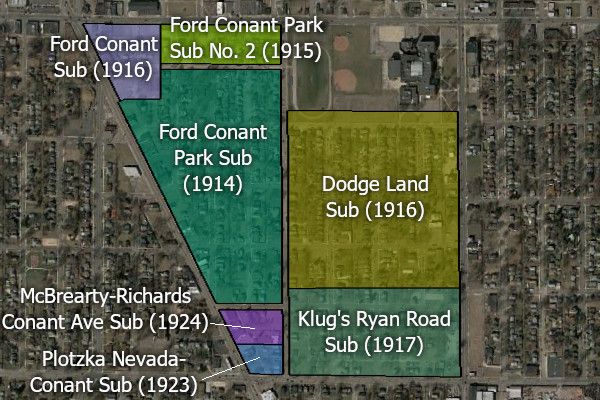

By 1916, annexation of this territory was inevitable anyway. The Wayne County Road Commission began paving Seven Mile Road with concrete all the way to Northville, increasing surrounding property values and spurring additional development. The color-coded map below shows the chronology of subdivision activity in the area.

Residents of Greenfield Proposal No. 3 voted 487 to 39 in favor of annexation on November 7, 1916. The measure passed in the unaffected part of Greenfield Township by 2,693 to 901, and by 80,818 to 11,388 in Detroit. However, city services were slow to arrive. As late as 1920, desperate property owners east of Woodward Avenue suggested that they detach themselves from Detroit and annex themselves to Highland Park or Ferndale. ("North End Men Plead Neglect; Plan Secession." DFP, Jun 23, 1920) It is not clear whether the threat had any effect. Another two years would pass before the district had adequate sewer service.

Hamtramck Proposal No. 1

"City Airport"

This one-square-mile territory in Hamtramck Township contained just a few small subdivisions by 1916. When originally proposed for annexation, this section was bundled with a larger tract of land in adjacent Gratiot Township.

Detroit voters approved this annexation by 86,648 to 12,640. It also passed in the unaffected parts of Hamtramck and Gratiot townships by 1,570 to 1,068 and 279 to 153, respectively. However, the results from inside the annexation district were ambiguous. Overall, the vote failed, with 91 in favor and 94 opposed. But taken separately, the votes were 25 to 16 in favor on the Hamtramck side, but rejected in Gratiot with 66 for and 78 against. The solution to this legal conundrum was to insert, at the end of the legal description of the annexation area, the following words: "excepting that portion of territory above described situated within the township of Gratiot." Thus only the Hamtramck Township portion of the area was admitted.

Hamtramck Proposal No. 2

"North Detroit"

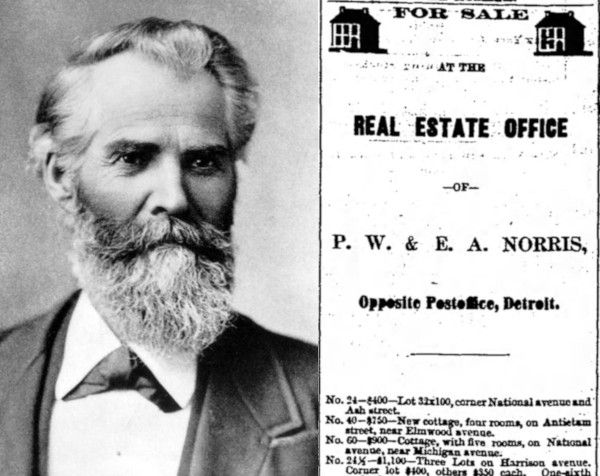

The best known early settler of this area was Colonel Philetus Norris, a veteran of the US Civil War who served as the second superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. After the Civil War, he was hired to drain a large, swampy portion of Hamtramck Township through a series of ditches leading to Conner's Creek. He evidently saw a lot of value in the land, accumulating hundreds of acres by 1867, when he established a real estate business in Detroit with his son, Edward.

In order to make his property accessible, Colonel Norris and a group of investors chartered the Detroit and Prairie Mound Plank Road Company in 1871, with the aim of building a plank road from Detroit to his land, and eventually through the villages of Warren and Utica in Macomb County. The toll to use the road was five cents, and it was heavily traversed by farmers bringing their produce to market in Detroit. The plank road's path is now part of Mount Elliott Street.

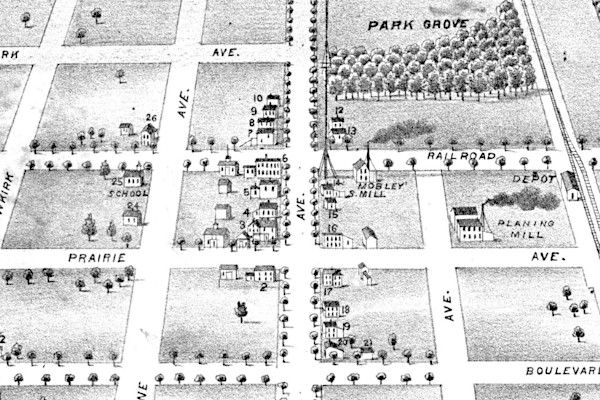

An additional connection to Colonel Norris' land came in 1872, when construction began on the Detroit and Bay City Railroad, running straight through his property. Colonel Norris constructed a depot next to the line, and the railroad company agreed to make it a station. Another road was added three years later, running west from the property to Woodward Avenue. Originally known as Norris Boulevard, this road is now East Davison Avenue.

After the railroad came through, Colonel Norris was ready to kick his village-building project into high gear. He built a home for his family at Iowa and Mount Elliot streets that year, leaving Detroit behind. He retained his real estate business, but exclusively dealt with rural properties after that point. In August of that year, Colonel Norris subdivided some of his land along the railroad into town lots and called it the "Village of Norris," although it was never legally incorporated as such.

The postmaster was even persuaded to shut down the post office at "Dalton's Corners" (present-day Van Dyke and Eight Mile) and reopen it in Norris instead. By 1876, the village was home to 250 residents, and contained "variety store, hardware and tin shop, meat market, two hotels, blacksmith, wagon, shoe and other shops."

Colonel Norris left his village in 1877 in order to accept the appointment of superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, a position he held until 1882. He died in Kentucky while on a research trip for the Smithsonian Institute in 1885.

Realtors began to take special interest in the suburban community during the economic boom of the early 1890s. "During the past eighteen months," the Detroit Free Press noted in February 1891, "acreage in the vicinity of Norris has been quietly bought up through the agency of T. H. Baskerville, Robert Thomas and others for various capitalists of Detroit and elsewhere." These capitalists rebranded Norris as "North Detroit," going so far as to officially change the name of the village's post office. ("A Big Week In Realty." DFP, Feb. 22, 1891.)

The Panic of 1893 apparently interrupted any major development plans, but by the 1910s realtors were ready to market new subdivisions in and around the settlement. In early 1916, a new street car line on Davison Avenue connected North Detroit with Ford's Highland Park factory, making it an ideal home site for Ford employees. One of the largest realtors to market property in North Detroit was Judson Bradway, who advertised "moderate but proper restrictions to protect your family in an all-American district." (Judson Bradway advertisement. Detroit Free Press, Aug. 31, 1919.)

As was the case in north Greenfield Township, this section of Hamtramck Township was becoming increasingly populated ahead of the availability of running water or sewerage facilities. Two months prior to the annexation vote, Edmund T. Paterson, president of the Detroit Real Estate Board, cited this public health hazard when promoting the annexation:

"At several points outside and adjacent to the city are already considerable centers of population which are already suffering for want of sewer and water facilities and fire and police protection. A small section of Hamtramck township adjoining Highland Park on the east now has within a few blocks about 2,000 inhabitants without police or fire protection and recently the health authorities have been worried about the spread of disease among these people. An outbreak of an epidemic here owing to the lack of sewerage would be a most serious menace to the city."

("Realty President Talks of Suburbs." DFP, Sep. 11, 1916.)

Coincidentally, Paterson and his brother, Horace, operated their own real estate firm, Paterson Bros. & Co., which owned several brand new subdivisions in this annexation area, southwest of Mound and McNichols. Some advertisements for Paterson's North Detroit subdivisions assured prospective home buyers that they would be buying in an "American neighborhood."

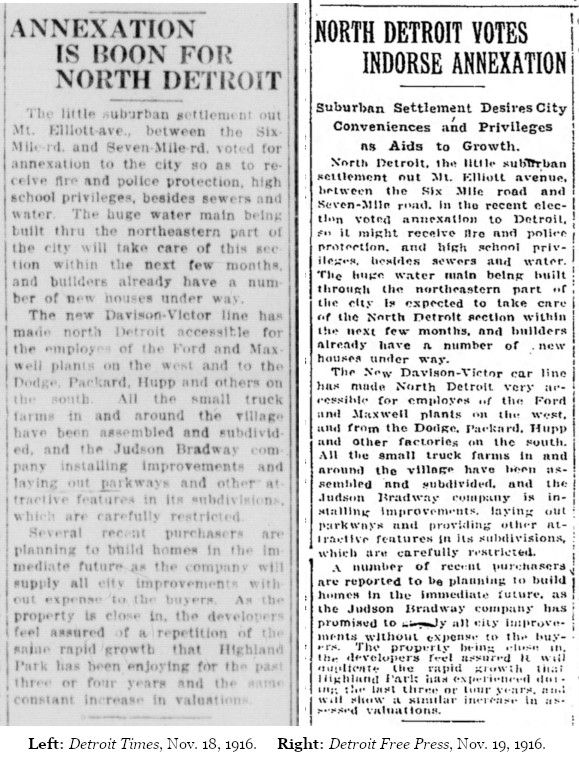

Hamtramck Proposition No. 2 was favored by voters in all three districts whose approval was required: within the annexation area, 181 to 134; in the township outside of the annexation area, 1,322 to 917; and in Detroit, 81,743 to 12,059. Days later, the Detroit Times reported, "All the small truck farms in and around the village [of North Detroit] have been assembled and subdivided, and the Judson Bradway company is installing improvements, laying out parkways and providing other attractive features in its subdivisions, which are carefully restricted." ("Annexation Is Boon For North Detroit." Nov. 18, 1916.) The Detroit Free Press printed a virtually identical article the following day — they were undoubtedly lightly rewritten versions of the same Judson Bradway press release.

One noteworthy neighborhood which would rise here some years after annexation is Conant Gardens, bounded by Conant, Nevada, Ryan, and Seven Mile roads. None of the subdivisions inside of this area were marketed by prominent Detroit realtors, which is probably why no racially restrictive deed covenants were placed on the properties. This lack of restrictions allowed Black Detroiters of means to build an upper-middle-class community here beginning in the late 1920s. By the 1950s, Conant Gardens had the highest median income of any Black community in the city.

Hamtramck Proposal No. 3

Of the six annexation proposals from Greenfield and Hamtramck townships, Hamtramck Proposal No. 3 was the only one to fail outright. Since it did not pass, and because no legal description of the territory seems to have been printed in any available newspaper, its exact boundaries are unknown. One newspaper article describes it as "a very small strip of territory in the northwest corner of Hamtramck township adjoining the Greenfield township line on the west, and the No. 2 proposition boundary on the south." ("Annexation Areas Now Confirmed." DFP, Nov. 16, 1916.) This very likely included the only two subdivisions in the area at the time: Burton's Seven Mile Road Subdivision (recorded by Wayne County in March 1916) and the Hamford Subdivision (recorded August 1916).

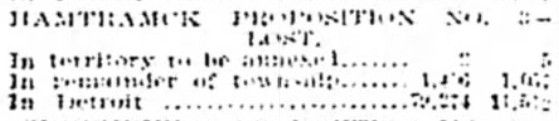

Only seven votes were cast inside of Hamtramck Proposal No. 3: two in favor of annexation, and five against. Detroit and the remainder of Hamtramck Township evidently approved the measure, but the only record found of the tallies (pictured below) is illegible.

Burton's Seven Mile Road Subdivision and the Hamford Subdivision were brought into the city as their own annexation following a vote on April 4, 1921. That time, only four votes were cast within the half-square mile area, and all were in favor of joining Detroit.

After Annexation

Following the canvassing and certification of the November 7, 1916 election results, the Wayne County Board of Supervisors filed their certificate and a copy of the annexation proceedings with the Secretary of State on December 11, officially completing the city's newest addition. Detroit had increased its land mass by nearly 50%, adding more than 21 square miles of territory at once. The assessed valuation of property in the city, which was $306 million in 1906, had increased to $1.2 billion after annexation. ("Detroit Now Has 70 Square Miles." DFP, Dec. 14, 1916.) The city limits reached Eight Mile Road for the first time, enveloping Highland Park and Hamtramck ever since.

The Detroit Free Press ran a special eight-page "Annexation Section" in its December 10, 1916 edition, consisting mostly of articles promoting the wonderful growth of Detroit and more than a dozen advertisements from local real estate firms. Of the ten articles with bylines, nine were written by prominent Detroit realtors:

Judson Bradway "Annexed Lands Aid Home Makers"

Edmund T. Paterson "City's Development Is Sure To Proceed"

Homer Warren "Prosperous Year Comes With 1917"

William H. Miller "Rapidly Growing West Highland Park District"

Harry T. Clough "Eyes of Outsiders Measure City Best"

Burnette F. Stephenson "Banner Business Year Is Coming"

Burt E. Taylor "Active Industries Swell Population"

Walter C. Piper "Wealth Is Likely To Reward Many"

Thad E. Leland "Expanding City Requires Realty"

One of the uncredited articles in this "Annexation Section" reported on English night school programs for foreign-born laborers in Detroit, which quotes at length an article entitled "Americans First" from a New York magazine. According to the unnamed Free Press writer:

"In Detroit big business men are no longer in ignorance of "how the other half lives," for the home of the foreigner is supervised and his life in the new world guided by a friendly, big brother's hand. Labor leaders have been far-sighted enough to realize that if the immigrant is left in ignorance of his adopted fatherland, he will, all unknowingly, perfect or injure the faculties at his disposal. In Detroit, non-English-speaking races are taught American methods in the night schools, so that they no longer blunder into danger and shatter the profits that their cheap labor rates may have accrued."

Another noteworthy (and uncredited) "Annexation Section" article discussed the importance of deed restrictions:

"One of the conditions that is becoming in evidence in Detroit is the creation of exclusive communities, or the building up of restricted subdivisions. In other cities these have prevailed in numbers, but in Detroit, for years, the Grosse Pointe settlement was the only one. Then came Bloomfield Hills and now a number are in the making.... There is nothing quite so nice as a settlement where the families are of a class, ideals are high and the beauties of life are reflected both in and out of the homes. It is a part of the greatness of Detroit that such communities are increasing and that there is such a demand for land where one may live among his own kind."

Post Script:

"How The Other Half Lives"

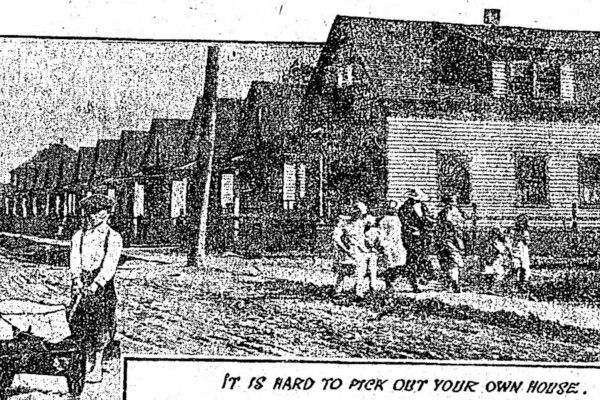

What was life like inside of a newly annexed part of Detroit in the 1910s? Areas where houses were built before utilities were available have already been mentioned, but the conditions in one new city neighborhood in particular had gained such notoriety that Detroiters began calling it "Hell's Half Acre."

Occupying about half a square mile around the intersection of Davison and Dequindre, the location offered plenty of cheap land only a 20 minute walk from Ford's Highland Park factory. At least 5,000 people lived here by the time of annexation, the vast majority of whom were recent immigrant laborers from eastern Europe and the Middle East. As one writer described the community: "Rumanians, Serbs, Turks, Armenians, Austrians, Bulgars, Montenegrins, Arabs and others, not overlooking a generous sprinkling of Americans, have been scrambled over the area until there is no telling how many nationalities may be found under a single roof, or how many tongues may be drawn into a discussion of affairs of mutual interest."

Unfortunately, because the township government had neither a building code nor the ability to fund major public works projects, the community was essentially a suburb that completely lacked running water, sanitary sewers, or utilities of any kind. Sewerage drained into cesspools or ran into ditches which discharged into Conner's Creek.

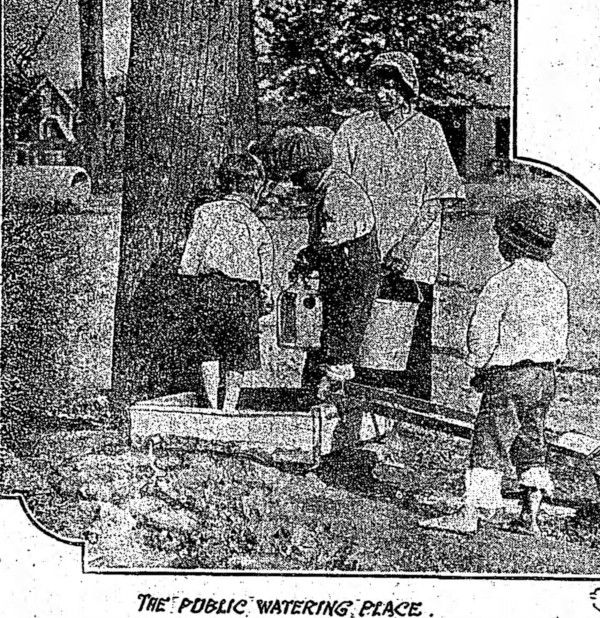

Prior to annexation, residents obtained drinking water from shallow wells "sunk only a few feet through the sand, with a strata of clay beneath, and were located in close proximity to cesspools that made the water unfit even for washing purposes, although it was used for cooking and drinking," according to a July 1917 Detroit Free Press article. The director of the Detroit Board of Health, Dr. James W. Inches, discontinued the use of these wells and installed a sanitary public watering station — and yet Highland Park supplied the water, because Detroit was still unable to. "Here the inhabitants flock for their daily supply. They come with buckets and bottles and cans and jugs.... It is no easy task, for the journey is often a matter of four or five city blocks, over unpaved roads where sidewalks are built in irregular sections."

Partly in response to worker living conditions like these, the Ford Motor Company established its controversial Sociological Department — the "friendly, big brother's hand" — in 1914. In addition to supervising living conditions, Ford's sociological inspectors also monitored employees' personal spending and consumption habits. Following the 1916 annexation, The Detroit Health Board was so overwhelmed by its attempt to serve "Hell's Half Acre" that it permitted Dr. Inches to swear in inspectors from Ford's Sociological Department as deputy city health officers. ("Ford Men Will Aid In Clean-Up." Detroit Times, Apr. 30, 1917.) The photograph below, taken by a Sociological Department inspector around 1914, shows the conditions of a Ford employee's home somewhere in metropolitan Detroit.

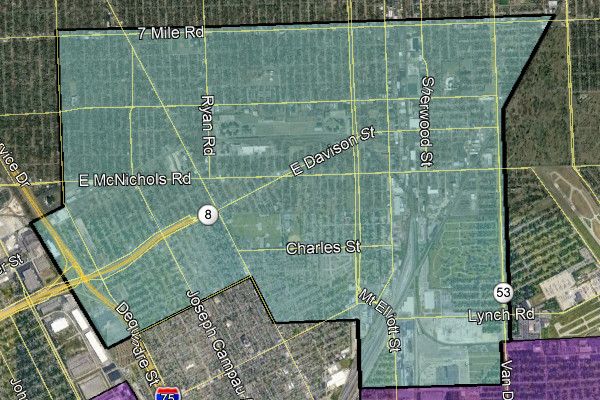

Some improvements came more quickly than others. In March 1917, the Detroit School Board ordered a ten-room addition for the Davison School to relieve overcrowding which had become so bad that students were forced to attend half-day sessions. The Health Board opened a baby clinic at Davison and Joseph Campau in August 1918, yet the community suffered an unbelievable infant mortality death rate of 166 per 1,000 live births as late as 1921. ("Fewest Babies Die On Street Called Healthiest Spot." DFP, Jul. 21, 1921.)

Typhoid fever and other communicable diseases flourished in the sewerage-filled ditches for years after annexation. Due to poor surface drainage, "water stands in the yards and surrounds the houses," according to a Free Press editorial. "In the summer time this district breeds clouds of flies and mosquitoes." ("Part of Detroit." DFP, Apr. 20, 1920.) When a city library was built on East Davison between 1920-1921, its sewer line had to be connected to Highland Park's system because there were "no sewers or water connections (to Detroit's system) despite frequent appeals made by residents there since the area became part of Detroit." ("Sister City Lends Sewer To Detroit." DFP, May 20, 1920.)

In order to fight for the basic city services, a group of concerned citizens organized the East Davison Avenue Improvement Association in 1919. Its president, William A. Ratigan, was the publicist for the Braun Lumber Company, located at the west end of the community. Among the association's first demands were a fire house with an apparatus and more fire hydrants, citing two instances where buildings had burnt to the ground before fire trucks could arrive. ("East Davison District Asks Fire Protection." DFP, Oct. 31, 1919.) Within a year, the Davison sewer was completed, Davison Avenue was partially paved, and the open sewerage ditches got a clean-up.

When the East Davison Avenue Improvement Association sponsored a parade in September 1920 to declare the "End of Hell's Half Acre," the community was still without adequate fire protection, police protection, storm sewers, gas lines, or even garbage collection. ("End of 'Hell's Half Acre' To Be Celebrated Monday." DFP, Sep. 13, 1920.) The neighborhood's first police station, Precinct 11, opened in a rented store on Davison Avenue on September 1, 1921. Still, by that late date, all streets in the neighborhood except Davison Avenue were impassable tracts of mud after a heavy rain.

While Detroit's realtors were gearing up for yet another annexation in 1921, a Detroit Free Press editorial pointed out that previous annexations have been "badly done ... as anybody can see for himself by looking over the large expanses of unimproved and vacant land already included in the area of Detroit." Less than half of the city's 1,500 miles of streets were paved, and large areas still had no sewer system.

The editorial cited Public Works Commissioner Joseph A. Martin, who claimed that the city's 81 square miles should have been able to accommodate up to 2,000,000 people. "Before any more outlying lands are allowed to become city accretions for the benefit of real estate projects or for any other reason, we ought to take care of the large chunks of ill digested territory we already have." ("Annexations That Can Wait." Nov. 2, 1921.)

The northern section of Detroit was finally furnished with water and sewer service by the summer of 1922. ("Detroit Finds Its Big Chance Out Woodward." DFP, Aug. 13, 1922.) For the conditions that developed in the East Davison Avenue area, there was plenty of blame to go around: Ford might not have built his factory in the northern suburbs; realtors might not have subdivided land into city lots decades before sewers were available; Detroit might have annexed the area before any building began (as realtors argued); Hamtramck Township might have found a way to halt building activity when the sanitation problem was noticed.

At least part of the blame can be placed on the shortage of labor and materials which came with the nation's entry into World War I, and the two-year economic depression that followed. In any case, it remains unclear how new annexations to Detroit could be justified at a time when thousands of city residents had already been languishing for years under dangerously unsanitary conditions.

This is how the city grew — messily, chaotically, and orchesterated by multiple parties each acting in their own best interest. While city annexations were very lucrative for the wealthiest of land speculators and real estate developers, often the people most desperate for city services — the entire point of the annexations — were the very last to benefit.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.