Last month, I marked Maurice Sendak’s yardzheit with a look at the legacy of Where the Wild Things Are. He would have turned 93 today.

Maurice Sendak wrote survival guides for the most vulnerable people in society, but disguised them as children’s books. He knew he couldn’t prevent adults from doing stupid and destructive things, so he gave children the tools to navigate a broken and unfair world. His later stories were not about following your dreams as much as confronting your nightmares with courage and strength and meaning.

Children know the world is scary. They don’t need pretty lies and hollow assurances that they know the adults themselves don’t believe. They need the tools, courage and honesty to make their own way in the world. This is what Sendak gave children, and the parents reading his books aloud often learned how to be less afraid, too.

Maurice Sendak was the child of European immigrants. He learned first hand how terrifying the world could be. On the day of his bar mitzvah in New York, his family finally got word — his grandfather had been murdered in the Holocaust. Soon, news arrived of other relatives lost in the camps.

The Holocaust demolished my family, my parents. I saw that, I was there, I was a child. I had to bear it even though I didn’t have any idea what it meant. What language was there to tell a child? None. That has stayed with me all my life. I was very much afraid when I was a child.

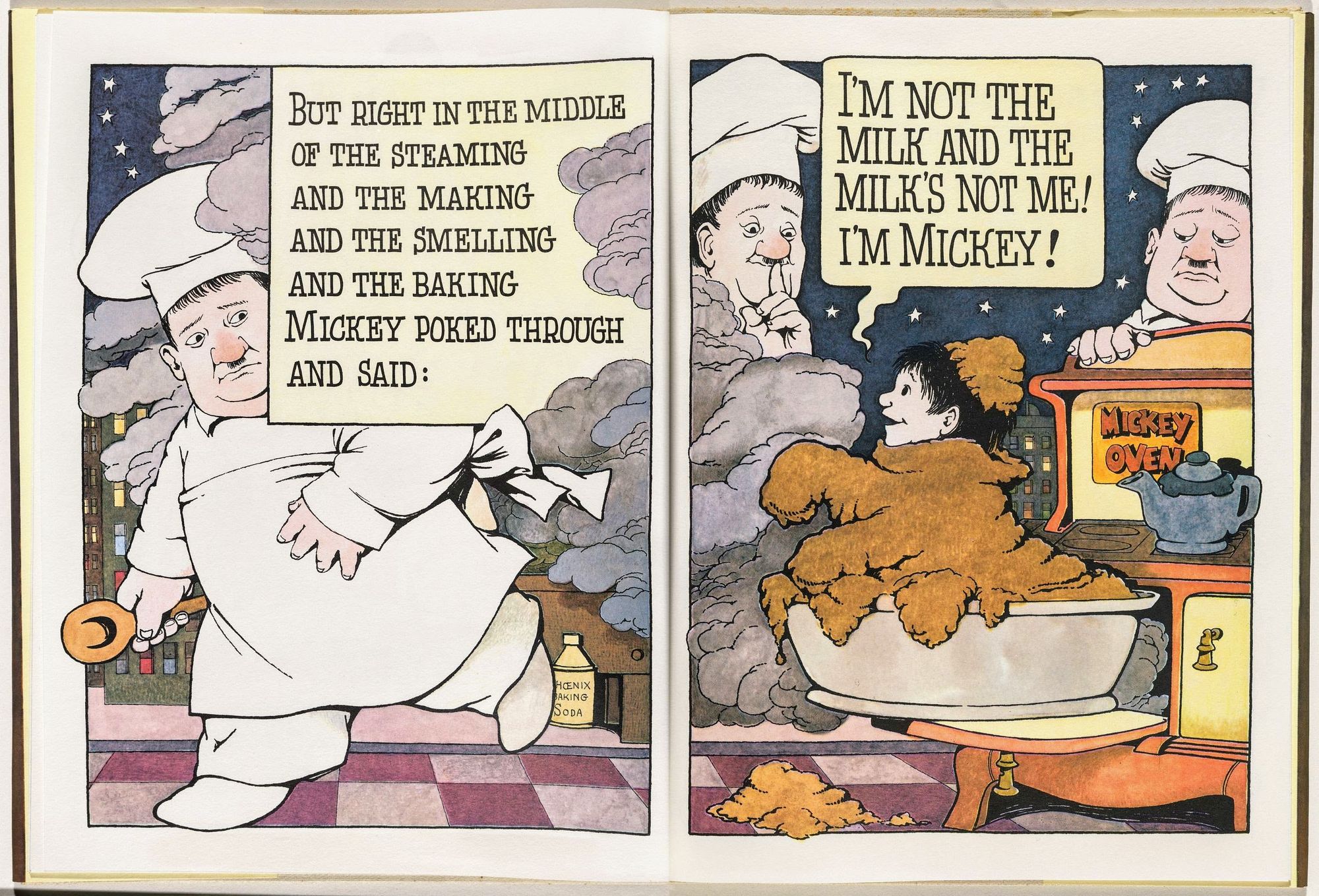

Sendak did not address the Holocaust directly in his earlier works, but there are intimations if you look carefully. In the Night Kitchen is a tribute to Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland, a Sunday comic strip he read as a boy, and to Mickey Mouse, his favorite character of the twentieth century. The story is about a little boy named Mickey who has some trippy dreams that are odd and a little scary, but manageable. He cleverly escapes the danger of the kitchen and wakes up safe and sound. He outmaneuvers three Oliver Hardy-looking figures with what can only be described as Hitler moustaches. They are trying to bake him in the oven.

His later works became darker and more explicit about the dangers that children face. The greatest fear that children have is being separated from their parents. He had been traumatized by the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and the images he saw in the newspaper when he was four years old.

Sendak understood that there were different kinds of separation, some that were physical, but others were emotional, and maybe even more damaging. His stories don't necessarily have happy endings, though some do. They have best possible endings.

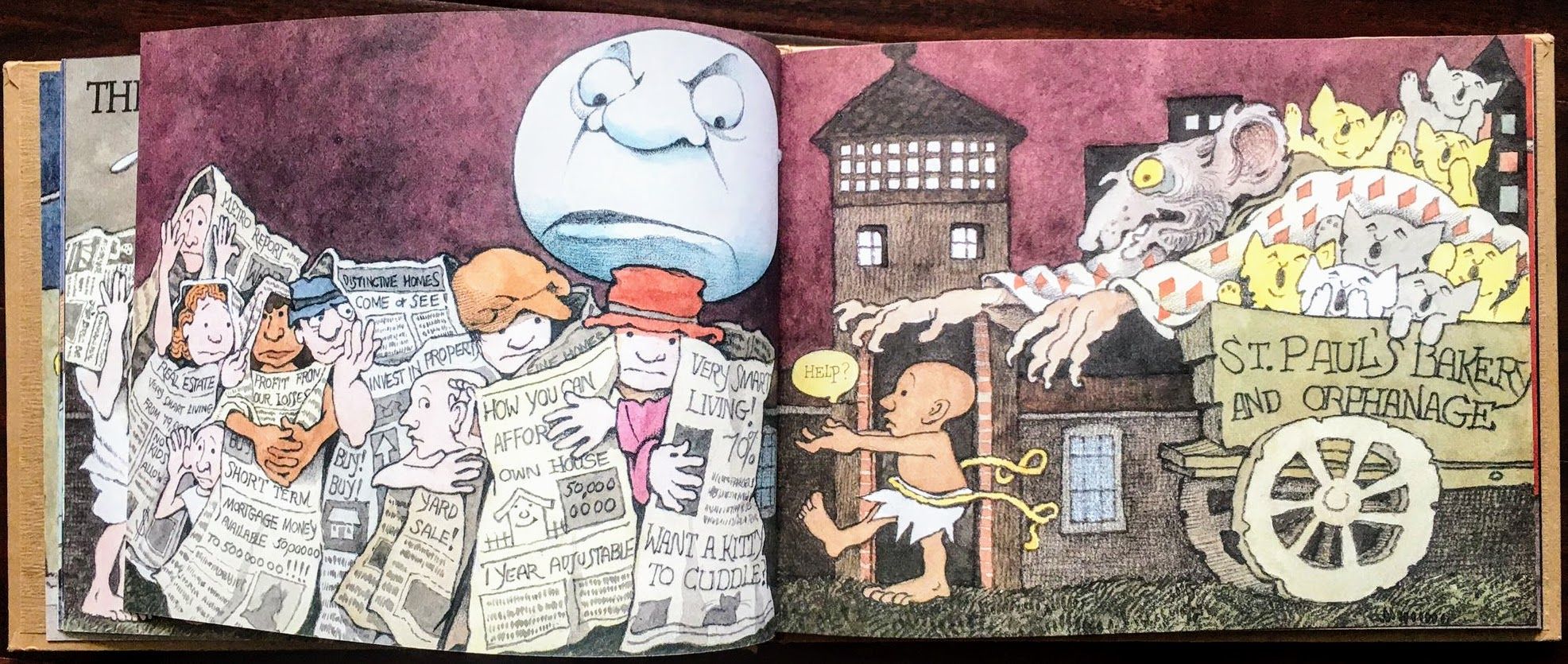

We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy

One of his lesser known but more controversial books is We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, about homeless children creating a way to take care of each other. It was deemed too difficult for children to handle, though few of the critics mentioned homelessness as something even harder for children to deal with.

He responded to the criticism:

Children get shot on the way to school, children contract AIDS, children are in the most vulnerable position imaginable ... If we don't look, and if we don't listen, and if we don't do something, kids will be lost.

Maria Popova wrote about the book, “Created at the piercing pinnacle of the AIDS plague and amid an epidemic of homelessness, it is a highly symbolic, sensitive tale that reads almost like a cry for mercy, for light, for resurrection of the human spirit at a time of incomprehensible heartbreak and grimness. It is, above all, a living monument to hope — one built not on the denial of hopelessness but on its delicate demolition.”

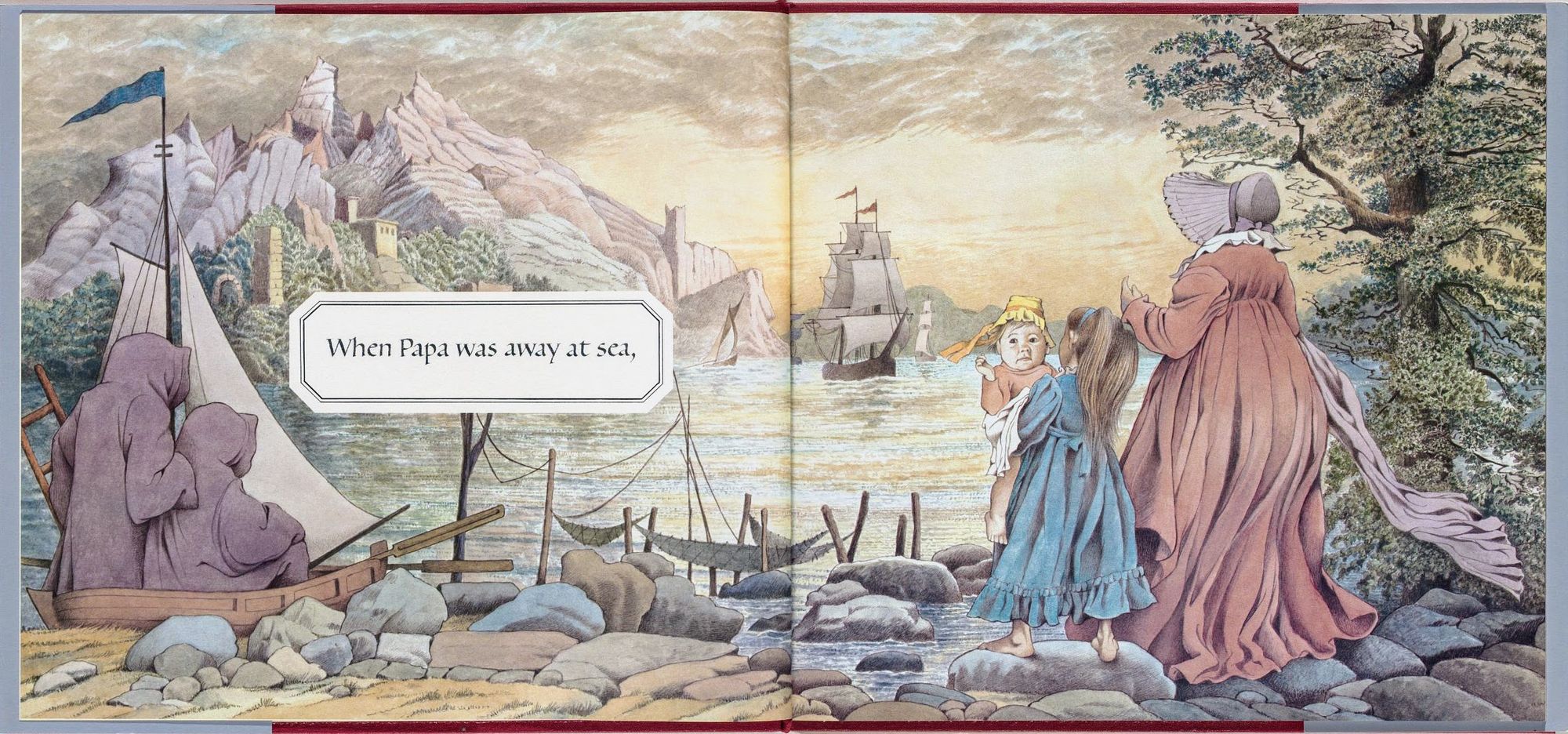

Outside, Over There

Outside, Over There tells the story of a family in the 1800s. The father, who is never seen in the book, must go to sea on a whaling ship in order to support his family. These trips were dangerous and often took years. He leaves behind a wife and two young daughters, Ida and her baby sister. His wife is distraught, nearly paralyzed in anticipation of the grief she knows is inevitable.

Ida takes care of her sister, even rescuing her from a kidnapping, and comforts her mother. Outside, Over There ends with a letter from the father sending word that he is on his way back. But given the length of time it would have taken for a letter to arrive, we do not know whether he makes it home. Ida continues her care for her family. She is not broken or angry because of it. She knows what she has to do and does the best she can.

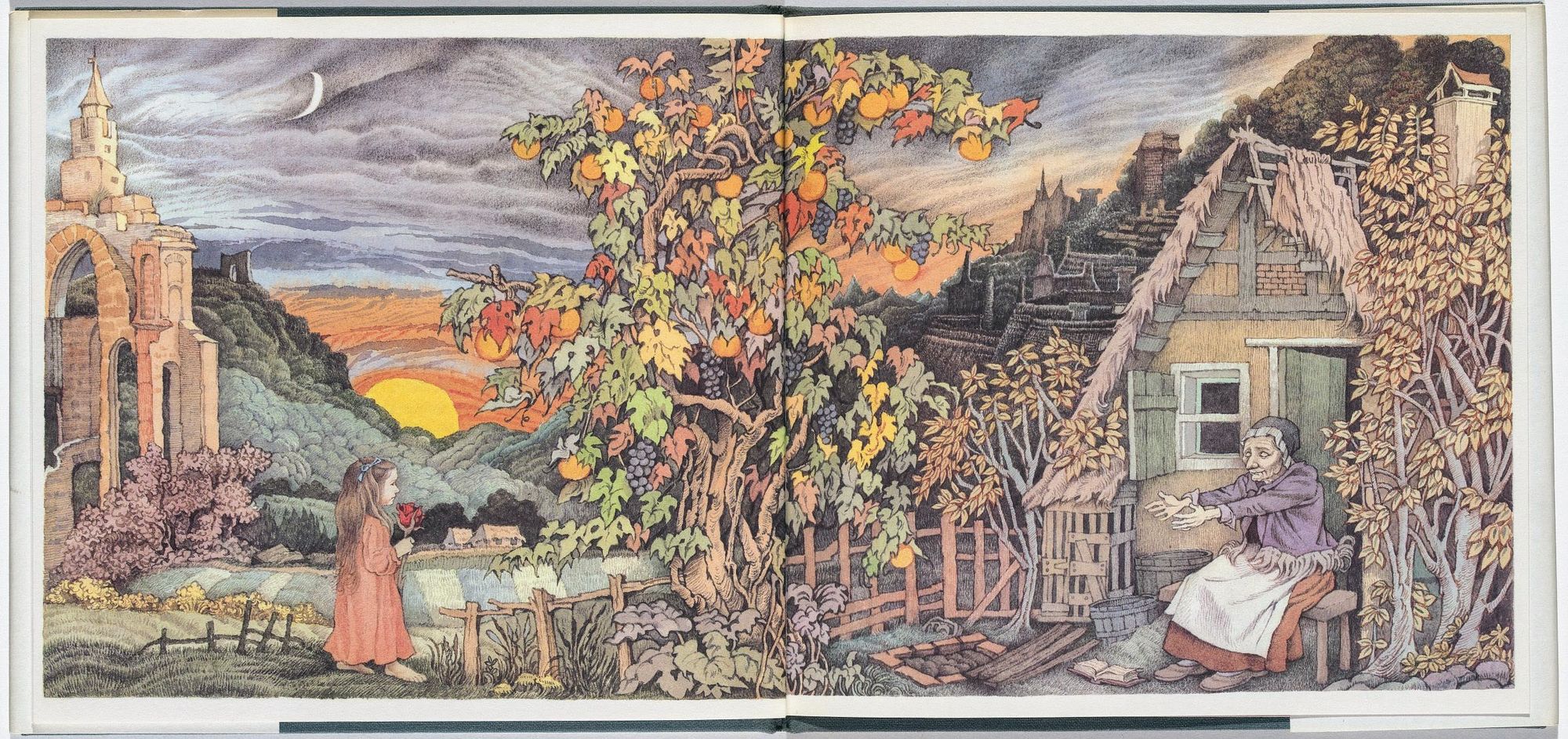

Dear Mili

Dear Mili was the first book of Sendak's to grapple with the Holocaust explicitly. The text came from a long lost story by Wilhelm Grimm. The Brothers Grimm made it their life's work to create the folk history of the German People, so a Jewish person illustrating their stories was neither the obvious nor most welcome choice.

Sendak illustrates Dear Mili beautifully, but subverts it with powerful pictures in the background, including Anne Frank, Auschwitz-Birkenau — and the Children of Izieu-Ain, slaughtered dispassionately by the order of Klaus Barbie, who noted in this diary, "This morning the Jewish children's home 'Children's Colony' in Izieu-Ain was liquidated. Altogether 41 children aged three to thirteen were arrested. Furthermore, it was possible to arrest the whole Jewish staff consisting of ten persons, including five women. Cash or other valuables could not be seized."

Brundibar

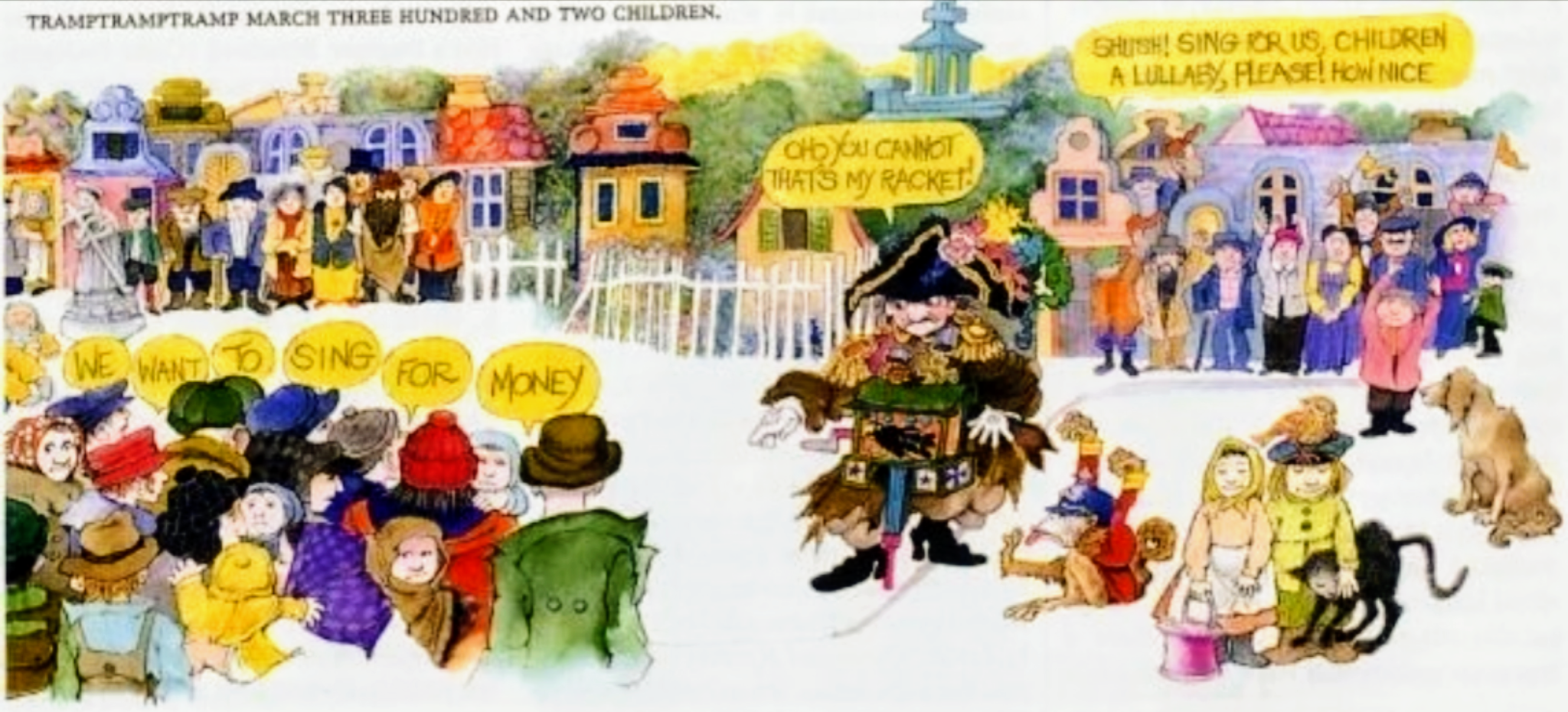

Sendak collaborated with Tony Kushner on Brundibar, both as a book and an opera, which ran off-Broadway in 2005. Their work is based on the children's opera by Jewish Czech composer Hans Krása. Written in 1938, Brundibár was performed over 50 times in 1943-44 by the children of Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín).

Brundibar tells the story of a brother and sister who need to get help for their sick mother and how they must defeat both the townspeople, who are indifferent to their mother's suffering, and the wicked Brundibar himself. The siblings succeed, even making the townspeople kinder, though Brundibar swears that he will return. The brother and sister are not Jewish, though many of the characters wear Yellow Stars. The fact that most of the children from the Terezín production did not survive lingers over every page of the book. Sendak was moved to see Jewish schools all over the world go on to stage productions of their adaptation.

In 1993, 30 years after Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak shared:

“Children surviving childhood is my obsessive theme and my life’s concern … These are difficult times for children. Children have to be brave to survive what the world does to them. And this world is scrungier and rougher and dangerouser than it ever was before … I want kids to know what the world is like. They are going to have to live in it!”

Thank you, Maurice, for helping kids survive to become adults without having to sacrifice their childhood to get there.

Rabbi Aaron Bergman is a rabbi at Adat Shalom Synagogue.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.