I have been coming Up North my whole life. It feels like home. The church that looks like a rocket launching as you drive up a hilly street I couldn't name or find on a map. The farmstand with the sweetest sweet corn every August on a curvy street I couldn't name or find on a map. That Japanese Maple tree at the corner of those two streets near the place that sells its own maple syrup and the horses that wear blankets when it's cold.

I feel lots of feels when I'm Up North – cozy, sun-kissed, serene, refreshed, sated, reclusive, hospitable. Adventurous not so much. Never been inside that church, never tried the farmstand currants, never asked the horses whether they plan to retire somewhere more temperate.

Nor do I come Up North to celebrate or explore my Jewish heritage. A rabbi visited once. She opened a window for me. It was not, however, a metaphor for a spiritual awakening but rather an actual window that was rusty and difficult to shut.

Now I find myself feeling far more MI-curious than I was, say, after the place nearby with the good tomato soup closed so we just stopped eating tomato soup.

Where did my new-found sense of wonder about this pleasant peninsula and my Jewish Joy™ collide?

South Manitou Island

For all the hazy mornings when the Manitou Islands lingered on the horizon and brilliant sunsets when it seemed like you could reach out and touch them, I'd never made it past Carlson's Whitefish and onto the Manitou Ferry.

But, as the saying goes, when your wife's working remotely – Costco table desk fits in Ford Explorer and guest-room closet once you take out the vintage Pack-n-Play – and family friends visits and someone else's kid (nice kid) sleeps over, you take the ferry to South Manitou Island.

Once we were finally on the open water, my priorities were primarily parental. No feet without shoes. No shoes with invasive species. No "Best Bloody Mary on Lake Michigan" on the island-bound AM leg of the trip.

I knew approximately nothing about the Manitou Islands – maybe because the legend of Mother Bear and her cubs is the only story sadder than The Giving Tree.

a brief history

8,000 years ago: Glaciers melt.

Next Thousands of Years: First Peoples hunt and fish on the Manitou Islands, never staying year-round for lack of large game and because it still sometimes feels like the ice age never ended.

1825: Erie Canal completed on time and with zero union grievances.

1830s: William Burton settles on South Manitou Island to refuel wood-burning steamships and get away from Vermont, where people are still talking about the War of 1812.

1800s: Cutting down trees and shipwrecks mostly.

1903: Czar Nicholas II exiles Joseph Rosen.

Didn't see that coming?

Imagine my surprise – getting towed around the island by a tractor, trying to convince someone else's kid (nice kid) that the blue athletic tape I had buried in my backpack is magic and will make her bug bites stop itching as long as she doesn't scratch the tape – when I hear about a Joe Rosen who wasn't Jo Rosen.

Joseph Rosen found his way to Michigan as a farmworker and then student at Michigan Agricultural College. In 1909, his father sent him 2,000 rye kernels from Riga, now the capital of Latvia.

Rosen Rye – a hybrid he created under the tutelage of Professor Frank Spragg – could more than double the yield of native rye but needed a space where it could grow without cross-pollination diminishing its unique qualities.

Recapping: 13,000 years ago, people schlepped from Asia across the Bering Strait near the modern Russia-US border, populated what we now call the Americas and lived alongside wooly mammoths and 200-pound beavers.

Then in the 1850s, a few families came to South Manitou Island from Bavaria by way of Buffalo to farm the land that had been cleared to provide fuel for the ships on Lake Michigan.

Then in 1917, as war and revolution scorched the earth in their homelands, the German farmers and Jewish agronomist came together on a four-mile-wide island by a bunch of sand dunes to grow the finest rye ever cultivated.

The Most Compact & Flavorful

Rosen (the rye) and Rosen (the guy) both stayed busy for the next few decades.

Rosen went on to direct the American Jewish Joint Agricultural Corporation, helping resettle 250,000 Jews displaced by the Russian Revolution on farms in Crimea and Ukraine in the 20s. During World War II, the British and US governments tapped him to explore the feasibility of British Guiana as a new home for Jewish refugees. Ultimately, he facilitated the settlement of over 700 German Jews in the Dominican Republic before passing away in 1949.

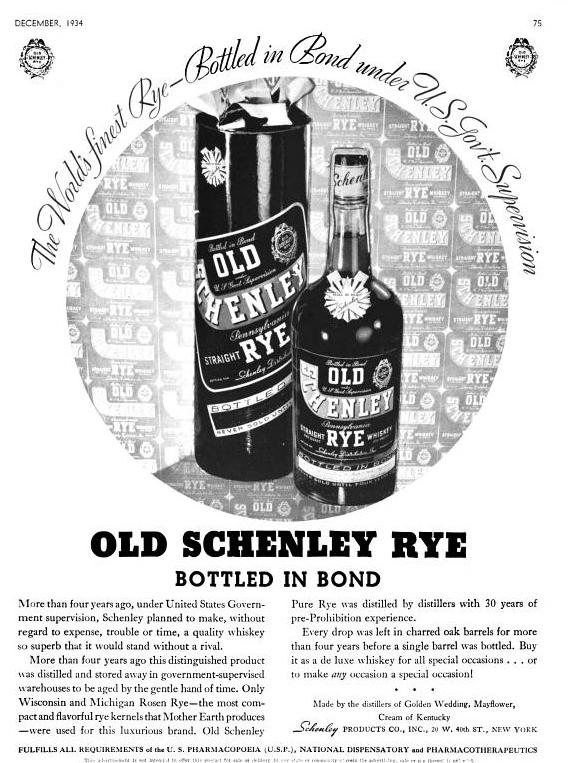

Rosen Rye made Michigan the largest rye producer in the country, dominating the Rye Championship of the United States and Canada. “Michigan Rosen Rye: the most flavorful and compact kernel mother earth ever created” became the selling point for Old Schenley Rye and for Michter's Distillery until 1970 – the same year the Manitou Islands became part of the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

Last year – with precious cargo from the USDA Seed Bank in Colorado and a permit from the National Park Service – Ari Sussman and Mammoth Distilling planted the first Rosen Rye on South Manitou Island since 1950.

There I stood, alone, before the small patch of Rosen Rye on Hutzler Farm. We shared the cool, quiet breeze under the midday sun.

Both of us Michigan born and bred and yet only because of the thousands of miles traveled and untold hardships overcome by our ancestors – equal parts fight and faith – were we able take root in this good earth.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.