On the 15th of Nisan, Passover 2025 began — and I found myself nearly 6,000 miles from the Motor City. This year’s seder, unlike all other nights, would take place not in the familiar spaces of Michigan, but beneath the windswept limestone corridors of Jerusalem’s Old City and surrounding neighborhoods. It was my first seder in Israel, and the significance of that moment coursed through the holiday.

As the full moon, rising after the northern vernal equinox, cast its silver light across ancient steps, I made my way to the nearby synagogue. There, by chance or fate, I encountered a friend whose family had helped found what would become Yeshivah Beth Yehudah. That brush with home was only the beginning. Thanks to friends from Detroit, I joined a seder just down the street from the Old City walls. Around that table, with other Detroiters, we were not just remembering our past — we were urgently reckoning with our present. The ancient story of Exodus echoed with new resonance: those yearning to be free, in a land still haunted by captivity.

This year, a lemon was added to the seder plate, a new symbol born of anguish and resolve. Rachel Goldberg-Polin — mother of murdered hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin and descendant of a family with Michigan roots across generations — had suggested its inclusion. “This lemon,” said Rabbi Gersh Lazarow of Melbourne, “is more than a symbol. It is a call to awareness and action. As its bite sharpens our resolve, may it kindle an unrelenting desire to see (the hostages) safely returned. May this emblem of captivity become a symbol of celebration at their release.”

In recent months, I’ve visited the scarred sites of the October 7th massacre. These are places where the land itself seems to mourn. Since that day, they’ve carried the soundscape of trauma: the silence of grief for the murdered, many still held in Gaza without the dignity of a proper Jewish burial; the sirens of rockets — thousands fired from Gaza, and now Yemen — that have pierced the quiet of synagogue services, jolted the nation from sleep at 3 a.m., sent entire neighborhoods sprinting to shelter, which I witnessed in the middle of the night, on the way to services and going to cover during Shabbbat prayers; and the weekly screams of heartbreak at Hostage Square in Tel Aviv, where families plead for the return of their loved ones during gatherings and rallies I attend throughout each week.

And yet, amid this grief, the soul and sounds of Detroit could be heard.

On the day earlier this year that it was announced that a few hostages would be released, my neighbors filled the streets with a song from RENT—a production shaped by Oak Park High School alum Jeffrey Seller. On a pre-Shabbat walk to Herzliya, the emotional weight of the week gave way to the voice of a beachside singer, pouring his heart into a Mike Posner song — he a graduate of Groves High School. I’ve heard Posner’s lyrics again at the gym, followed afterward in cafés by the unmistakable melodies of Allee Willis, Mumford High Class of ‘65. Bars along the streets and beaches blast out the familiar lyrics from Detroit-native Eminem. On Purim, concerts packed in thousands to celebrate the festivities in costume; and the most coveted of these events this year was funded by Wiz, a five-year-old Israeli startup whose cybersecurity solution Google offered $32 billion to acquire; it was filled with well known stars across Israel singing the anthems of Rochester Hills’ own Madonna.

The fingerprints of Detroit are everywhere here: in the Detroit Pistons broadcasts lighting up gym TVs at dawn; in the "Detroit" sweatshirts spotted on strangers who tell me their families once started companies such as Faygo back in the Motor City; in museum placards, library dedications, and university programs underwritten by Jewish Detroiters whose impact spans oceans and generations.

With so many threads tethering this land, you'd almost expect an entire orchestra to break out in a Motown medley.

And that's exactly what happened.

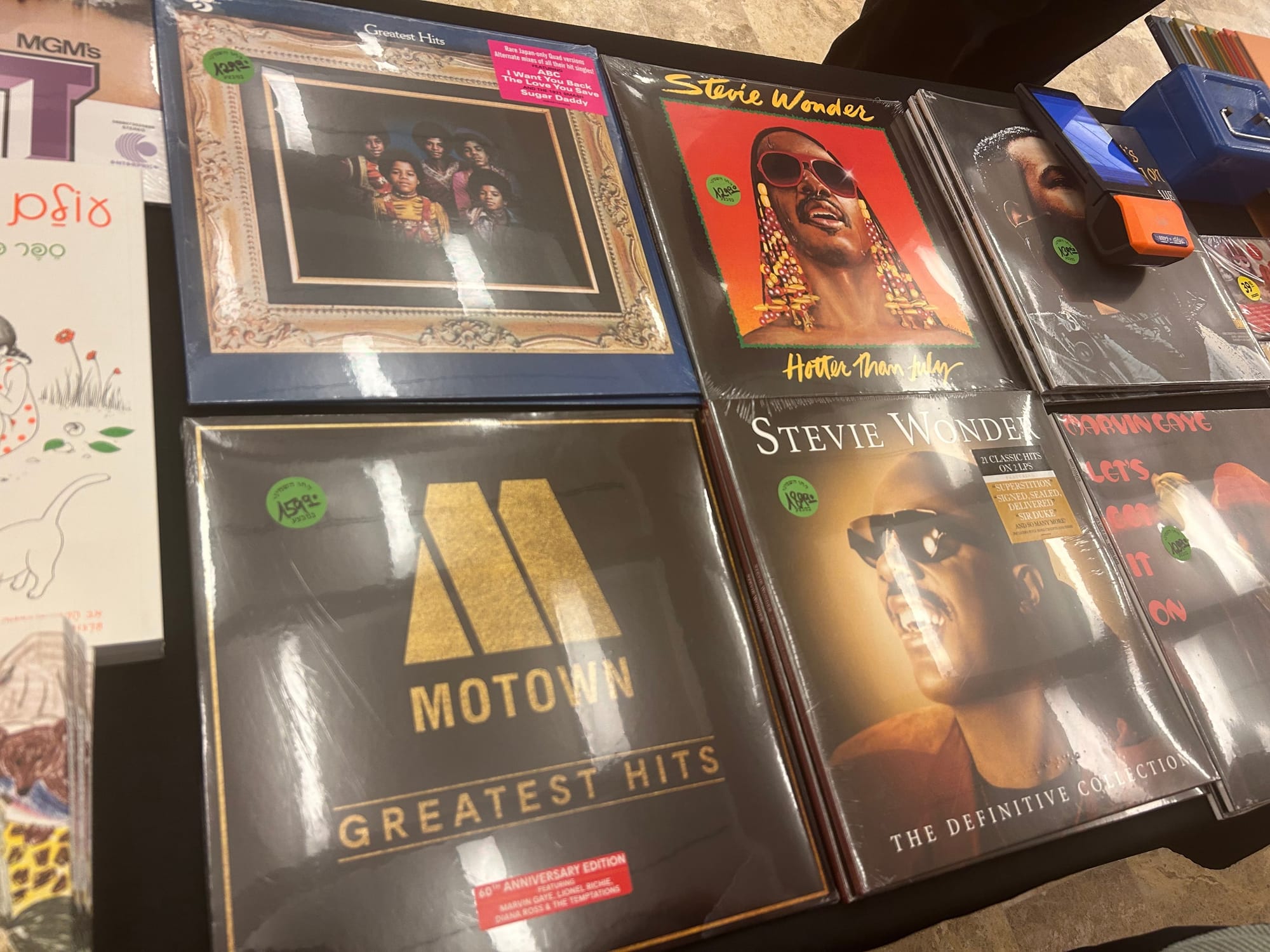

In the hours after Passover, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra invited me to a concert unlike any other: a celebration of Motown’s greatest hits. The first “Motown Party” had sold out swiftly. So they brought it back. Again, not a single empty seat remained. Israeli singers, artists of African heritage, jazz musicians, and the full force of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra converged on stage to honor an era, a sound, a spirit.

I may have been the only Detroiter in a crowd of three thousand and fifty, but when the first notes of Stevie Wonder rang out, when the rhythms of Marvin Gaye and The Jackson 5 filled the hall, it felt like every soul in the room belonged to the Motor City. People rose from their seats, dancing down the aisles, rushing to the front to celebrate songs that defined an era.

When I first met Berry Gordy Jr. in person, I understood his legacy as an entrepreneur. But in Tel Aviv that night, as the Philharmonic lifted his music into the Middle Eastern air, I witnessed how the sounds of Detroit — the rhythm and spirit — impacted music lovers globally.

Soon after, the siren for Holocaust Remembrance Day would pierce the air.

On Yom HaZikaron, thousands of young adults packed a standing-room-only event at the local museum to hear firsthand testimony from a survivor of the Holocaust. Across Israel, hundreds of intimate salons convened, drawing citizens together in remembrance of the Shoah. At Hostage Square, a solemn ceremony unfolded within a ring of posters bearing the faces of the captives — signs soon to be featured in a screening at Detroit’s JCC.

I didn’t make it back to Michigan this Passover. But the deep connections between the communities abounded during the holiday in ways both purposeful and unexpected. In Jerusalem, and during a rare respite at the Israel Philharmonic, a part of Detroit visited Israel.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.