Ten years ago, give or take, I wrote my first article for the Detroit Jewish media. It was an exploration of tattoos in Judaism — a topic that was already trending then, and which has become downright trendy today.

I talked to rabbis from across the spectrum of observance, reassuring my readers that (no matter what their mother told them) they absolutely could be buried in a Jewish cemetery. I remember my own Rabbi at the time catching me in the temple hallway just before Shabbat to say “I read your piece. It was pretty okay! You should know that, biblically, the biggest prohibition is on tattoos for foreign gods and those that commemorate the dead. We talk a lot about tattoos being forbidden in Judaism, but really, those are the ones that are named as sinful.”

Whelp. Call me a sinner.

No one needs to read about think-piece about just how brutally 5784 (okay, fine, October 2023 onward) has been for us as Jews. You already know. You’ve lived it: the grief and fear, the anger and isolation. The disorienting conviction that half your social circle wouldn’t necessarily say they want you dead … but wouldn’t take time off work to help you wash the graffiti off your synagogue doors either.

Such is the pain — emotional and sometimes physical — of navigating all this loss. And I don’t only mean the macro-level loss of October 7th either, because so many of us are processing that paradigm-shifting, existential grief while also navigating the very ordinary, rather mundane sorrows of losing a grandparent, a spouse, a friend … or even losing someone we’ve never met but who we still looked up to as a shining example of what life as a Jew could be. You might be wondering what any of this has to do with tattoos.

Like I said, I’m a sinner.

I started 2024 with 12 tattoos. My artist describes them as “sticker book art,” meaning that I don’t have carefully curated sleeves, covering my limbs in flowing, coherent, unified ink. Nah … I have a dozen small designs scattered across my body like those puffy, sweetly scented stickers we all collected as children. There’s no logic or organization to the gallery on my body. Each piece (ranging in size from an inch to larger than my palm) stands alone, unique in intention and narrative. My ink isn’t a novel, but rather a collection of vignettes. The stories that make up my life my life, however disjointed, are written on my skin.

The pomegranate with the verse Isaiah 43:2 that I got when my young son was on the cusp of death.

The mirror on my hip with the phrase “know before whom you stand” inscribed in Hebrew by an artist working out of a literal cave in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The image of my grandfather’s wedding ring encircling a pendant he bought for my grandmother, just above my heart. That was the first “sinful” ink — a tribute to the dead that I was warned away from.

And here we are again. Because some events — the sickness of a child, a pilgrimage to Jerusalem — must be inscribed not only into memory but, for some of us, into flesh.

I was in Israel again this past May. My partner and I were walking through Tel Aviv. It's his favorite city on earth, renowned for it’s Bauhaus architecture. We stopped short, speechless. On the wall across from us was a flour paste poster by the artist who goes by YiddishFeminist: an anatomical heart, bandaged and hurting, but sprouting olive branches and set against the backdrop of one of the White City’s iconic buildings.

Perhaps in isolation, we would have admired the piece, commented on how effective its strikingly simple black line drawing was, and kept walking. But, covering the wall on either side, above and below this unbroken, still beating heart were dozens and dozens of hostage posters. We just stared. And then I told him that this would be my next tattoo. And the man who loves clean, bare, mid-century design and hates the messiness and color of tattoos? He nodded silently in agreement. I texted my artist from the sidewalk in Tel Aviv. And a few months later, just days after the anniversary of the October 7 attacks, the achingly simple but resonant sketch was traced onto my shoulder blade.

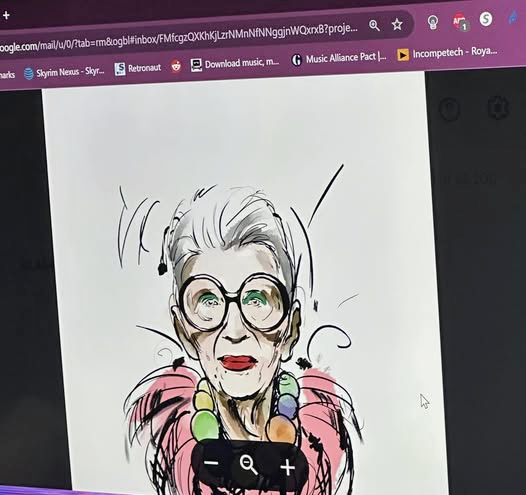

That’s not the only tattoo I got this year. Back in early March, several months before we took that walk through Tel Aviv, one of my heroines passed away. Iris Apfel lived to be 102 years old, so I couldn’t say that she was taken too soon. But her presence — the way she moved through the world, all flashing color and plain-spoken authenticity — that was a loss I felt deeply, even though I’d never met her. Iris was an interior designer by trade. She wasn’t beautiful. She used to say she had something so much better than prettiness … she had style. It was only later in life that she became a style icon. Her commitment to living well and leaning into joy, without fear of what others might think or what “good taste” might dictate was a huge inspiration to me. Watching her thrive in leopard print and feathers well into her 90’s gave women like me a roadmap for how to age — not gracefully, but fearlessly. Reject the paradigm that women of a certain age were meant to retire graciously and discretely from view to make space for the sparkle and shine of the young. Iris, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, showed us that life doesn’t fade into black and white as we grow older. I texted my artist the day the news of her death was announced. And a few weeks ago, a watercolor illustration of Iris, wrapped in beads and boas, adorned my right forearm.

All this isn’t intended to rationalize my tattoos. Folks who find them halachically transgressive shouldn’t be persuaded otherwise; those of us still striving towards observance are going to make our own compromises anyway. After all, the prohibition against getting tattoos for the dead makes a lot of sense. Torah tells us not to carve our flesh for the dead because scars are permanent and we should not fixate on what is gone.

Judaism does not allow us to wallow in grief, turning backwards towards our loss until we calcify in place. We sit shiva for seven days, and then we leave the house, and we walk. We are meant to keep moving forward and return from the valley of of the shadow of death back into life, carrying their memory with us. That’s why we say Kaddish — a prayer not of grief but of praise and affirmation — for a lifetime after the shloshim period ends. That’s why we light candles. Rather than narrowing our gaze only to their absence, we affirm the blessings that their lives afforded.

That’s what my tattoos do for me — they let me bring the lessons of those who have left us into the future with me, every day. Pride and hope. Intrepid authenticity. Strength and wisdom and joy in the darkness. And above all? Life.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.