On Sunday, May 8, 1910, hostilities erupted along Hastings Street, the Detroit neighborhood thousands of Jewish immigrants called home. Orthodox women rioted over the high cost of Kosher beef. Prepared according to the dietary laws laid out in the Torah, Kosher beef is always more expensive than non. But that spring, Kosher beef prices jumped 250 percent to eighteen cents per pound — far outstripping what working-class Jews could afford.

Detroit’s Jewish community blamed the inflation on Kosher butchers’ greed. The penniless butchers blamed the outrageous price of local cattle. The real culprit was Chicago’s National Packing Company, an unregulated conglomerate of five US meat-packing firms. The monopoly’s owners manipulated prices, putting heavy pressure on the third of the market they did not control — including the cattle used for Kosher beef. Everyone, Jewish and non, experienced high beef prices in the early twentieth century. But no one understood why.

As the Detroit Jewish community’s food shoppers and preparers, the women were the first to notice the price hike. They organized protests and a boycott of Kosher beef. Twenty-year-old Rebecka Possner, a Russian emigree, was the face of the movement. Incredibly, at age seventeen, she had led a walkout at the American Cigar Company factory in Philadelphia, successfully agitating for better working conditions. Now she lent her expertise to Detroit, telling the press, “We want no trouble and will have no trouble. We will win peaceably, but we will win.”

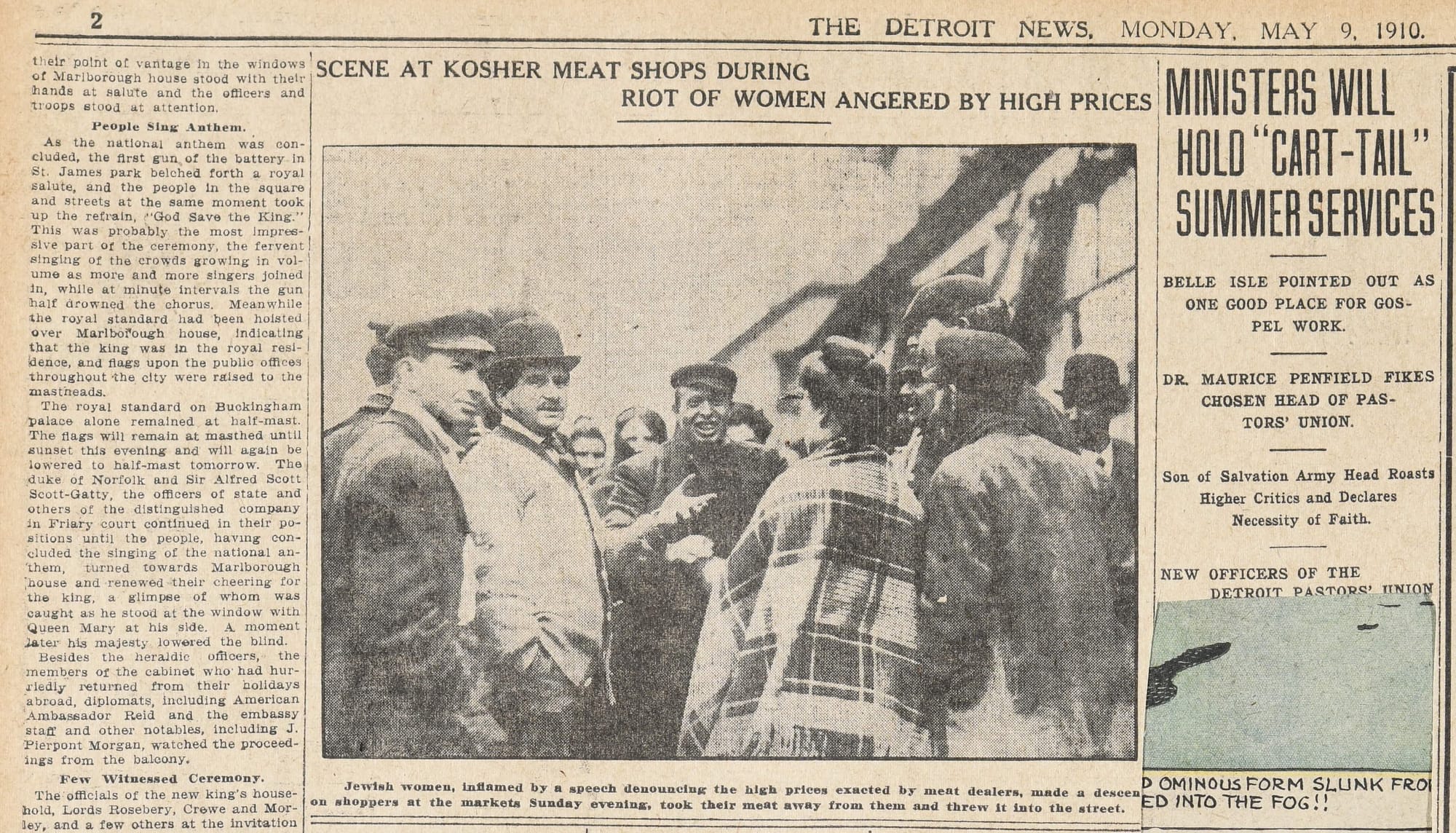

Despite the boycott, Kosher butchers remained open, selling to customers of greater means. The agitators fought back, seizing boycott breakers’ purchases and dousing them in kerosene. When even that tactic failed to stop all sales of Kosher beef, the boycott devolved into a riot. Remarkably, no one was injured, property damage was modest, and no arrests were made.

The riot spurred the Jewish community to reach a solution quickly: co-operative Kosher meat markets required to sell beef at rates midway between the original and inflated prices. The first location opened Friday morning, May 13. Although the meat was poor quality and not deboned before weighing, the price was right. By noon, all 2,200 pounds of its stock had been sold. Possner felt victorious, telling the community, “I am sorry [the boycott] resulted in a riot. But we will forget that. We have won our struggle.”

Detroit’s Jewish women won the battle. But they could not win the war. Trust-busting President Theodore Roosevelt would begin to dismantle the National Packing Company only in 1912. The process would drag on for another decade, as would nationwide unrest over beef.

After the riot, Rebecka Possner and her husband Harry opened a neighborhood restaurant. Widowed by 1916, she continued running the business long enough to appear in the 1920 census, before vanishing from the historical record.

Learn more about Rebecka Possner and the Detroit’s Kosher Meat Riot in “In the Neighborhood: Everyday Life on Hastings Street,” JHSM’s exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum, April 20 – July 14, 2024.

.png?itok=TOsKhqCO)

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.